藝評

繪描咖的日常作業 (Rex Chan - the Sketchomaniac: An Ethnographic Study)

黃小燕 (Phoebe WONG)

at 12:50pm on 5th January 2026

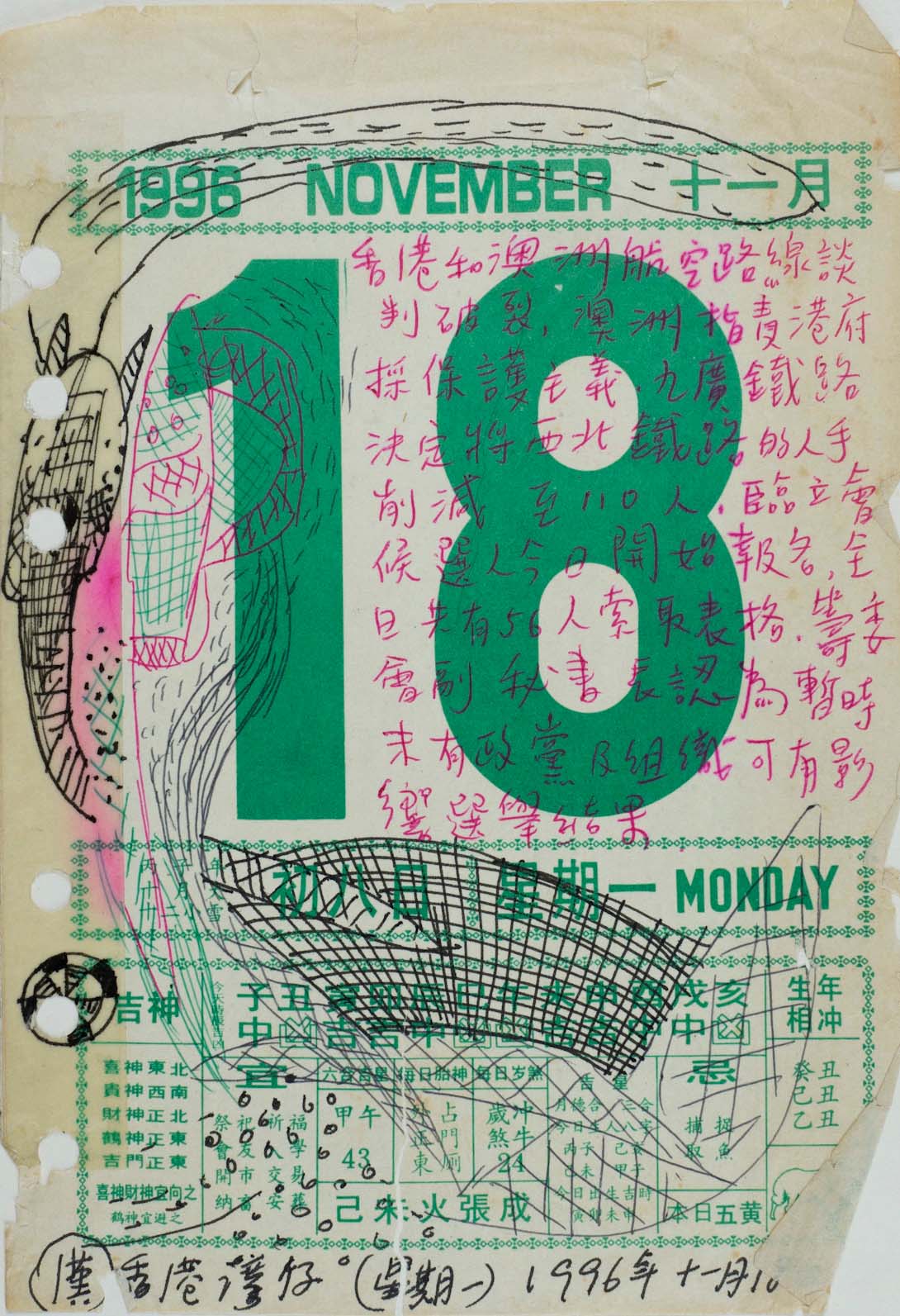

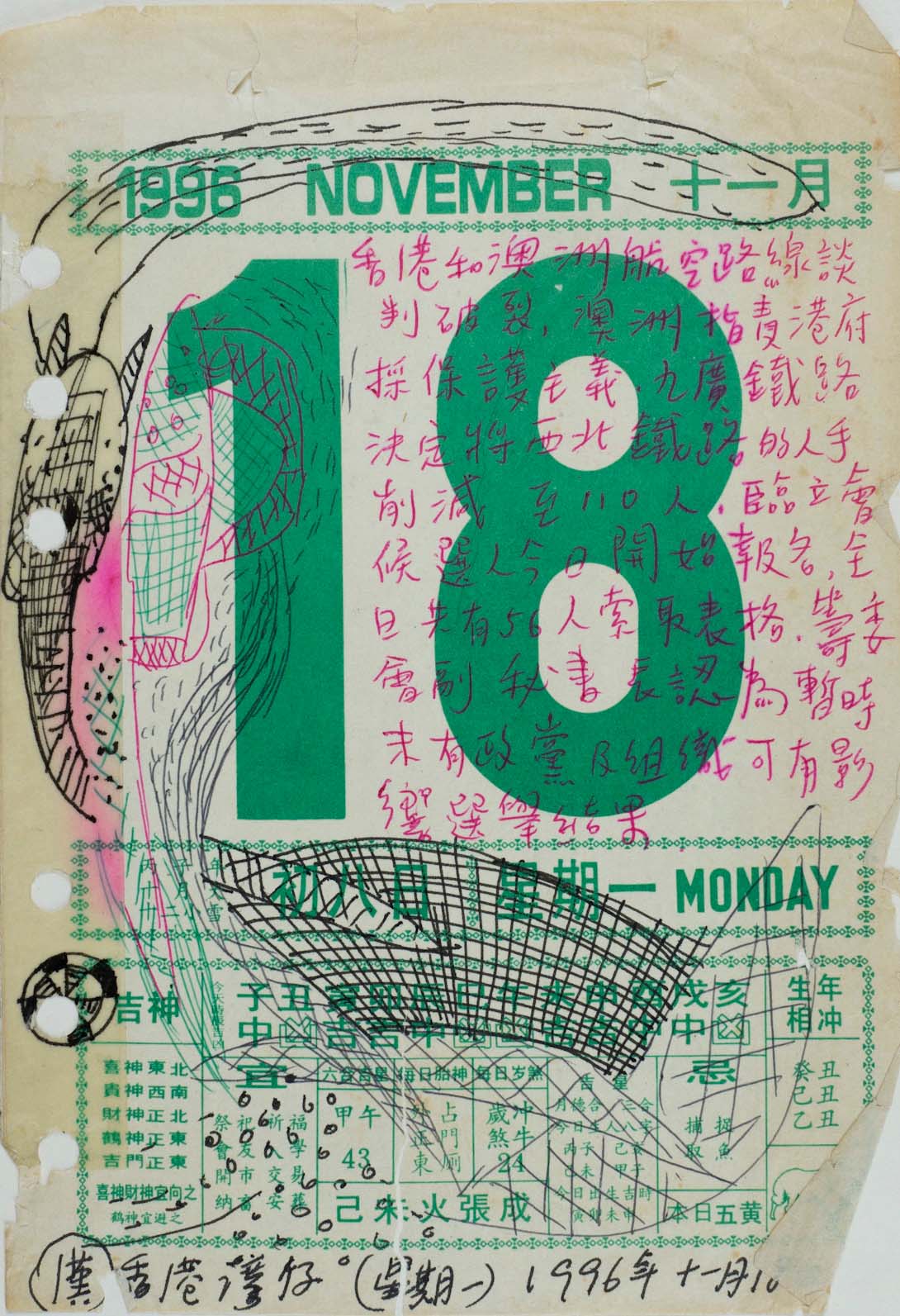

封面圖片:陳漢標 ,《1996年11月18日》。現成物拼貼,35.5(長)x 25.4(寬)厘米。1996年。

Cover Image: Rex Chan, 18 November 1996, found object collage, 35.5 cm (length) x 25.4 cm (width), 1996.

(Written by Phoebe Wong, Rex Chan the Sketchomaniac: An Ethnographic Study looks into the prolific drawing practice of designer and artist Rex Chan, who works across sketching, memory-sketching, drawing, and painting. This piece was originally commissioned by To Art House, edited by Joanna Lee. The author has been granted permission to publish it on the AICAHK website; with thanks. In Chinese & English - SCROLL down for ENGLISH).

繪描咖的日常作業 (Rex Chan the Sketchomaniac: An Ethnographic Study)

黃小燕

拉開圖櫃的抽屜,堆滿速寫簿、各種各樣大大小小的繪描,手繪的、非手繪的,平面的、立體的。說到畫,身為設計師的陳漢標(Rex),游走於速寫、默寫、繪描、插圖、繪畫之間。

速寫(sketch)、默寫(sketching by memory)、寫生(life drawing)、插圖(illustration)、草圖(layout),甚或繪圖(rendering),這些美術詞,有時可以互通,細分下來,又有些許差異,但都可統屬於繪描(亦稱素描)(drawing)之下。繪描之於設計學生,一如自由書寫之於小說家,是一種自我表達,也是一種預備狀態。

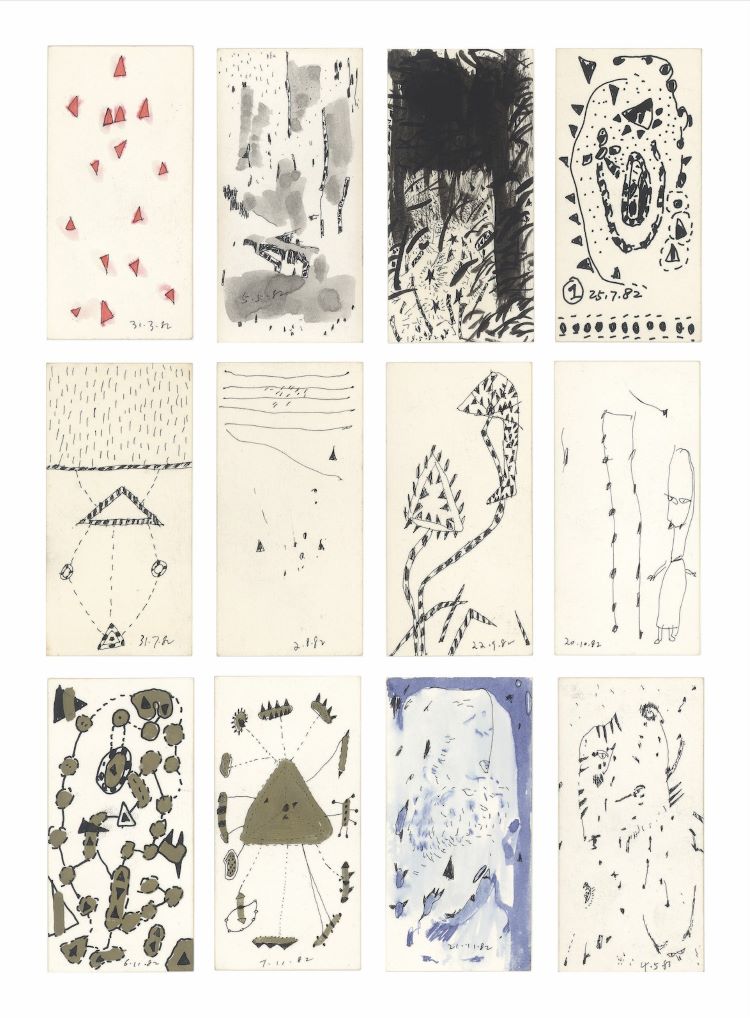

在這些數不勝數的繪描中,有三批繪描作品,相當引人入勝。一:卡片,主要創作年份從1982至1986年,之後斷斷續續至1989年,累積下來不少於3000張(圖一);二:1989年的鉛筆素描,超過三十張;三:印刷紙品拼貼,1996年起創作,至今約有240張。

(圖一:陳漢標的速寫卡片。圖片由作者提供。)

就這三批繪描作品,我開始與Rex對話。除了挖掘這些創作的來由、故事和方法,我尤其想了解他的設計師背景與他多樣化的繪描實踐的關係。與Rex細談下來,很多事情沒有簡化的、必然的因果關係,頂多只可讀出某種相關性;有些更是淹沒在記憶的深處,即便找到的線索,可能也只是草蛇灰線……。無論如何,得從Rex的設計師背景說起。

Rex在高中修讀文科,自修美術,1977年考入香港理工學院(理工)設計系。他一心一意想讀設計,是因某年暑假課餘報讀青年中心設計班播下的種子。設計班的導師是藝術家李其國,藝術與設計兼修,也是香港視覺藝術協會(VAS)的會員。[1] 縱然Rex上李其國的設計班時間不長,但這段經歷為他打下扎實的設計基礎及堅定的意志,使他意識到設計是一條可行的謀生之路。

1976年,他參觀了在理工校園內第一次舉行的「理工設計」畢業展;[2] 家住深水埗,跑去銅鑼灣華都酒店(Hotel Plaza)看VAS的展覽。Rex是透過李其國而知道VAS的。Rex今天回看,創立VAS的那一代藝術家經常談論「造形藝術」,嘗試另闢新奇,多運用平面的、有機體的造形(organic and graphic form),作品具象但不全然寫實。Rex認為自己的作品,也具備這些特質。

1979年,Rex在理工設計系完成了基礎設計文憑課程,獲得合符升讀高級文憑班的成績,但讀了半年後,由於感到課業的新鮮感不足,且外面工作機會多,便決定輟學就業。談到設計系的老師,Rex能一口氣說出十多位老師的名字,這些老師輩(在他心中)的份量不言而喻。[3]當中,Rex覺得跟郭孟浩(蛙王)之間「最有化學作用(good chemistry)」。初識蛙王,早在李其國的設計班,李曾帶學生到元朗參觀蛙王的藝術活動。後來,他們在設計系再次遇上。Rex憶述,在理工時期,郭孟浩採用開放式教學法。在以教雕塑為核心的課堂上,會教紮作、雕圖章,任何立體創作都可以嘗試;珠寶設計作業容許同學製作各種配飾,特點是大號且誇張,有同學甚至製作了道士帽;交上作業後,蛙王還帶領同學巡行去彌敦道。另有一課happening,蛙王自譯為「客賓臨」,同學在未完全建成的尖東一角放火燒東西。Rex自言對蛙王的教學「信服」,也「練大了膽」;愛雕印章,也是受到蛙王的影響。

說到七、八十年代學設計,離不開要學繪描,能夠畫好人物、器物、環境和空間,是成為設計師的基本要求。在香港理工大學的文獻裡還能找到1980年代老師用中文編寫的「繪描」教學筆記。[4] [5](圖二)教學筆記如是解釋:「繪描是最能傳達出藝術家情感的一種繪畫。因為它直接出自藝術家的手,是直接移譯,所以他與藝術家內在的意象距離最近,每一筆線條都是藝術家把存在於內心的意象轉變為繪畫形象的紀錄。」

這份教學筆記中的「移譯」說,強調了身(手)與腦(意念、意象)的連接與轉換,但僅為移譯說出一個輪廓。這讓我想到大陸畫家劉小東,他將人物寫生視為藝術行動 (life drawing as artistic action),但劉小東似乎只是把「移譯」的表現性外顯出來。直至讀到英國藝評人約翰・伯格(John Berger)寫他鍾愛的素描,哲理、形象兼備,才好像把「移譯」說透了點。放棄繪畫轉向藝評的伯格,終其一生,仍熱愛(人物)素描,從無間斷。伯格如是說:

圖像製作始於現象質詢和符號標記。每一位藝術家都會發現,素描——當它是一項即時活動時——是雙向的過程。素描不僅是測量並且記錄,而且還是接納。當看見的密度達到一定的程度,人們就會意識到同等強烈的力量,透過他正在仔細觀看的現象,向他襲來。[⋯⋯]這兩種力量的邂逅,以及他們之間的對話,並不提出任何問題或答案。這是一場凶猛狂暴又無法說清的對話。維持這一對話有賴於信仰。就像在黑暗之中挖掘洞穴,在現象之下挖掘洞穴。這兩條隧道相遇並且完全接合,[精彩]的圖像就誕生了。有時對話是迅捷的,幾乎轉瞬即逝,就像某物的拋擲和截獲。[6]

就算未能把「移譯」說透,至少也是一種註解。對,是之一。

(圖二:1980年代香港理工大學老師的「繪描」教學筆記。圖片由蕭競聰提供。)

有一段頗長的日子,Rex天天都畫卡片sketches。按他所說,那些日復日的小練習(drawing something)是隨手就畫,不用想的;筆(線)隨手走,畫得快,畫得多。一個晚上,能畫「一打半打」。我試圖追尋他創作的本意,不果,他忘記了最初是怎樣開始的,也許,不過是剛巧買了印章小卡,晚上有閒,隨畫而安。

Rex先後畫過兩種尺寸的小卡片,其中7.6 x 3.8厘米的印章小卡,較一般名片修長而顯得雅緻。畫咭片,Rex要麼摸索造形,畫有機體線條為大宗,要麼把玩物料,反覆畫,反覆試。習慣用水筆或原子筆,時而加點色,偶爾會先塗上色塊、從留白的負空間經營造形,畫面時滿(淋漓色墨中經營主體)時空(只有一條線),亦有富設計味的圖案。值得一提的,是Rex愛用0.1針筆(technical drawing pen)來描綫,為利索而穩定連貫(consistent)的幼線而雀躍。愛用(懂用)針筆來繪描的,大抵只有設計師。

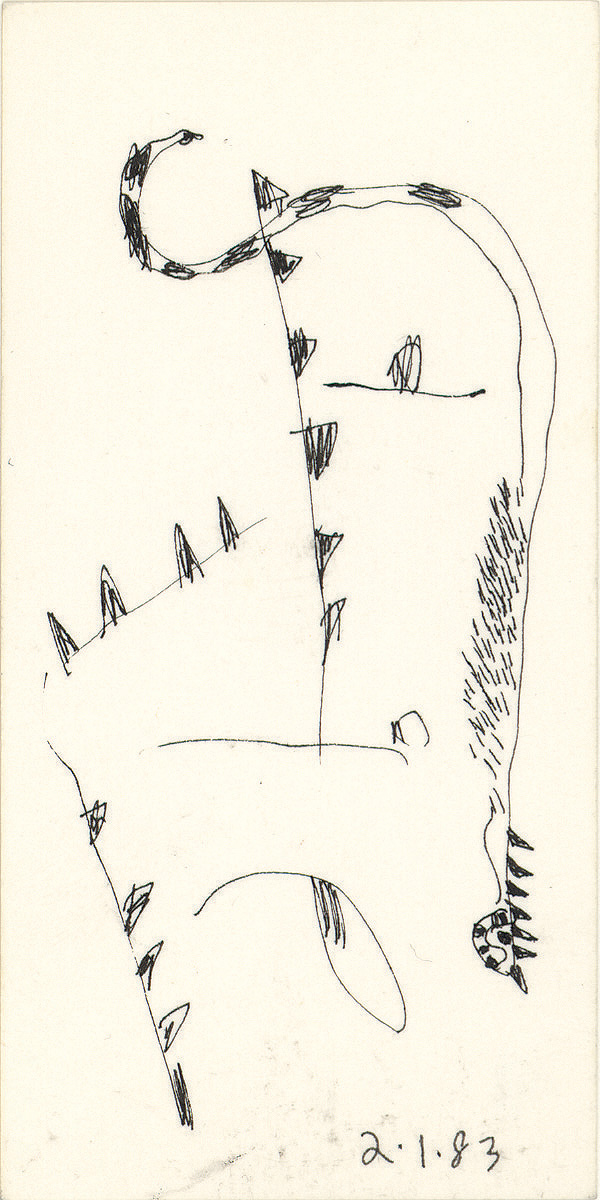

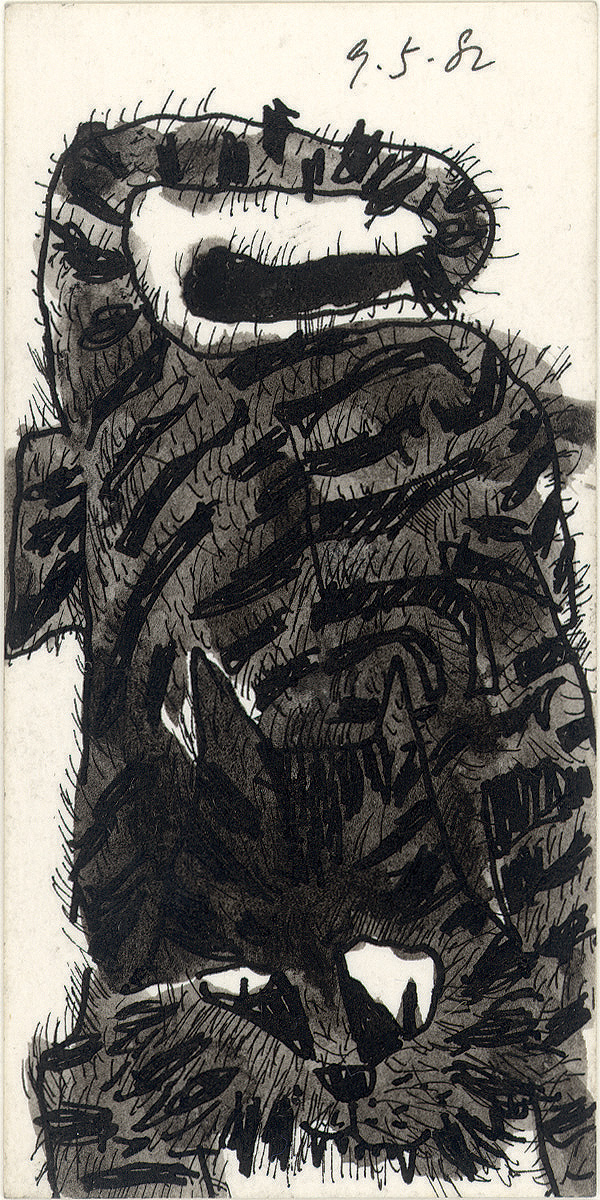

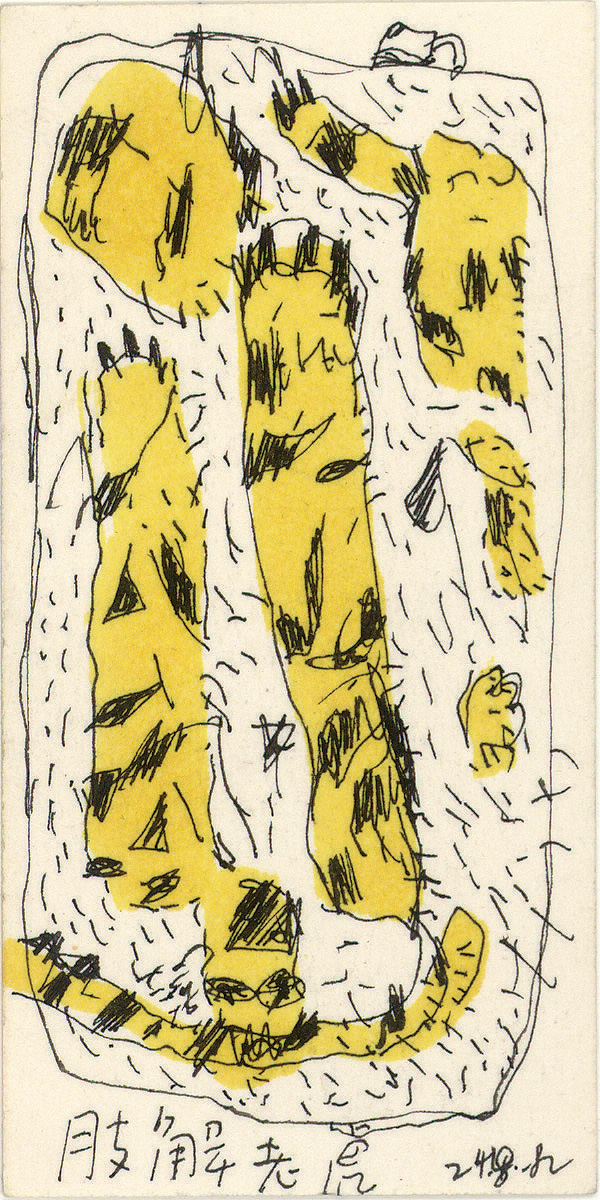

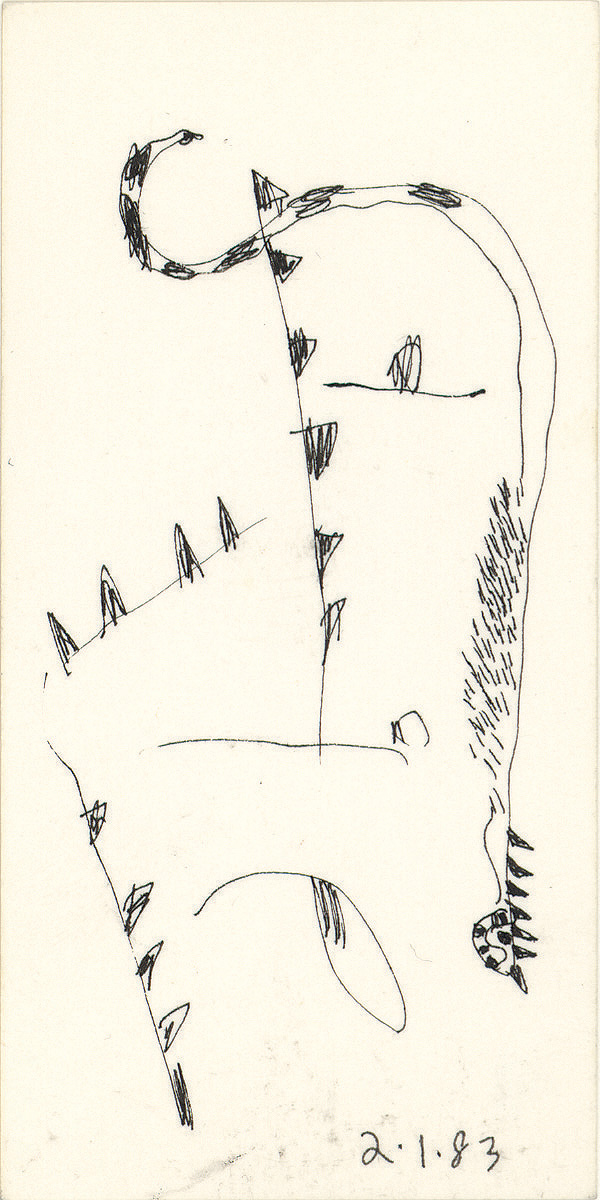

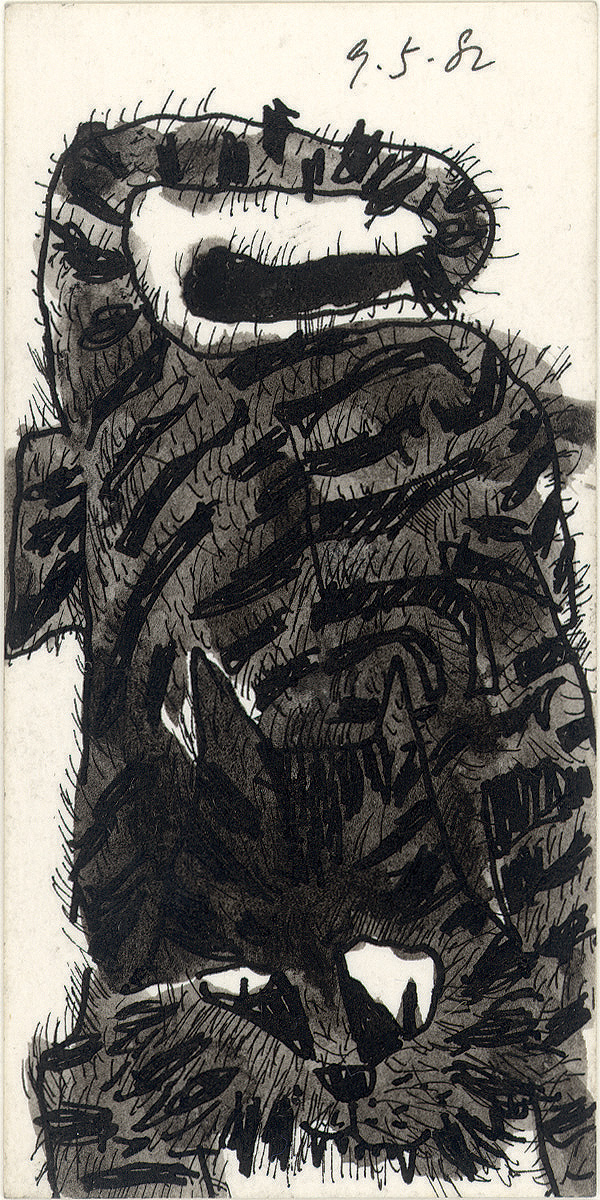

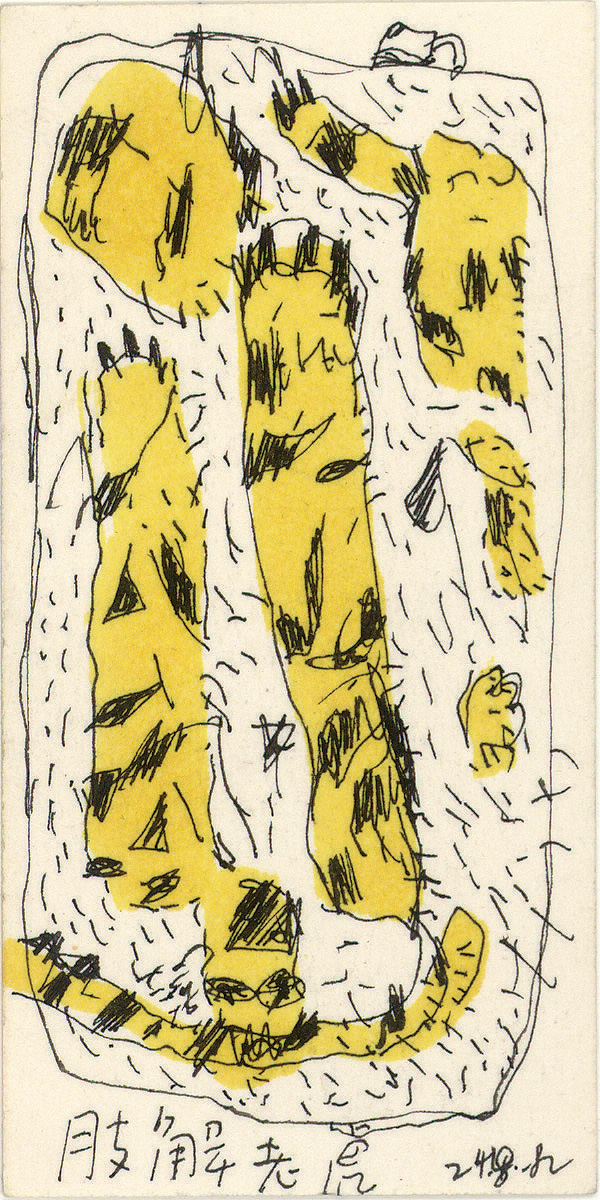

畫些甚麼呢?題材雜糅,但以人物和動物為大宗。人物的原型可以是生活中碰到的陌生人,可以是流行文化中的偶像,也可以是憑空想像而來,一經默寫處理,都帶點類型化(generic)。動物之中,有些是怪異物種,他早在這個時候就開始描畫山海經式的怪異物種:三眼長尾的半人半獸,四足飛鷹、鳥頭魚身 ,怪樹神獸 ,遞漸浮現紙上。動物之中,老虎一畫再畫,單是1982年,就畫了不下五十幅,而且風格多樣:大寫意、漫畫化、圖案化、民俗風,具象、抽象、局部、全貌,不一而足。(圖三、四)Rex筆下的老虎從來不兇猛,沒有張牙舞爪、沒有王者震懾之姿 ,有時更帶點拙稚氣息。日期「1982.08.24」卡片上寫著「肢解老虎 」,(圖五)我恍然有悟,在反轉老虎形象之外,圖像解構亦是他所以畫的旨趣。

(圖三(左)、圖四(中間):陳漢標。虎主題卡片。紙本速寫,7.6(長)x 3.8(寬)厘米。1982至1983年。)

(圖五(右圖):陳漢標。《肢解老虎》。紙本速寫,7.6(長)x 3.8(寬)厘米 。1982年)

此外,那些刺狀物反覆出現,有如一個個構件,像有待綴句成章的元素。這些呈三角形的小刺,有時只由線條構成,有時呈小色塊,有時是背景的一部分,有時又化身為老虎的爪子,有時候成了後現代設計(如Memphis式設計)的元素,更多時候是千姿萬態的觸鬚或藤蔓的突刺。顯然,這些刺狀物是荊棘的借代,成了他後續繪畫的重要元件,甚至母題。(圖六)(在Rex的巨幅畫作中,大號的荊棘以各種形態堂皇現身,但這已超出本文的討論範圍。)

(圖六:陳漢標。刺狀物主題卡片。紙本速寫,各7.6(長)x 3.8 (寬)厘米。1982至1983年)

Rex嗜畫,是一頭繪描咖,但寫生從不是他那杯茶,他只曾乘工作之便,在香港藝術中心上過人體寫生工作坊。當我形容Rex為默寫控時,他似乎又不以為然。不愛看電視的他,夜晚挑燈作畫,興頭一到,就記下白天所見所思,這是visual journaling,用畫圖作視覺日記。寫生和默寫看似相反,而Rex的小卡片揉雜速寫、默寫和繪描,游曳於圖像筆記和創作記號之間 。對照伯格所說的素描所蘊藏的能量交換, Rex在夜裡踽踽而畫的默寫和繪描,就是集記憶與思緒躍動的自我對話。

香港藝術中心前展覽主管陳贊雲曾這樣解讀Rex的畫作:「他的畫作刻畫人的孤立狀態,並引領觀眾遁入一個象徵性的虛幻世界,那裡充滿奇異植物和物種,它們通常被放大到比真人還大,顯示不朽的存在感。至於他的繪描,是創意湧現的迅速記錄,洋溢奇思妙想和驚喜。」[7] 陳贊雲心清眼亮的分析,一則直接指出繪描是一種筆記,一種notation;陳贊雲的原文選用「notation」一字,別具意味,這字的意涵很豐富,可解作記號、標記、註解、記錄,以至音樂用的譜號。另則,這段話間接帶出:繪描是經營大畫的注腳,就是這些繪描,厚積薄發,會給轉化或再一次移譯到大幅度的畫作之中。

本身也是設計師的文化人李念慈,曾在《星島晚報‧星期日雜誌》(1988年9月11日號)刊載過Rex的繪描卡片,並稱之為「日常作業」──Rex工餘自己給自己作業,一給就三、五、七年。李念慈欣賞這些作業的「即興」、「自由無拘束」⋯⋯[8]

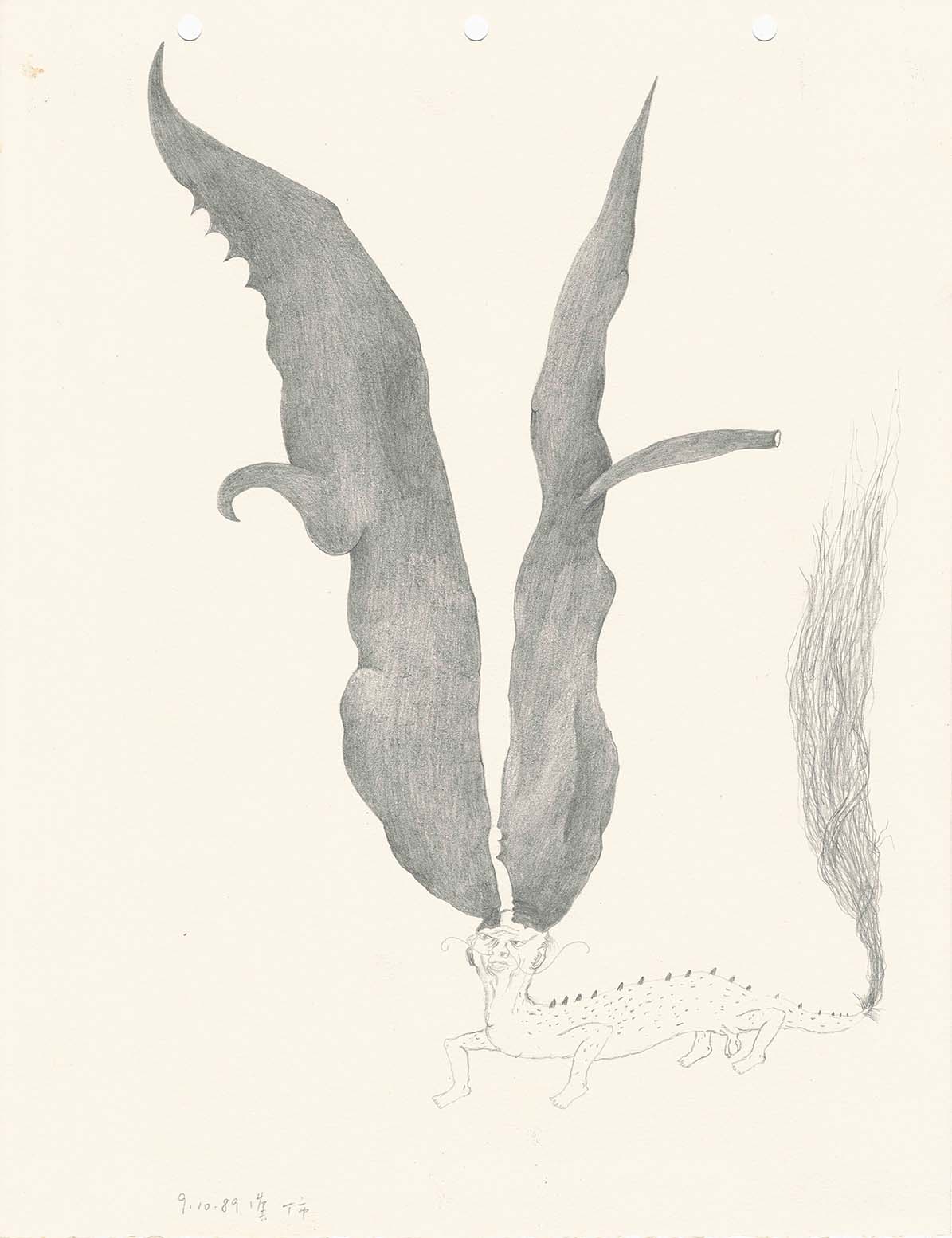

這些小卡呈現率性,爆發原始能量 ,共冶一爐美醜⋯⋯它們積小流而成江河。至於1989年為展覽而展開的鉛筆素描,Rex說是衝着速寫式小卡而做的,即是,他要「慢畫」,「慢畫」成為這批鉛筆畫的前題,他要觀照以至超越自己的耐性?那時候,他身處香港移民認為悶出鳥來的加拿大。這系列的素描是他扺埗後頭三個月過渡期內完成的。

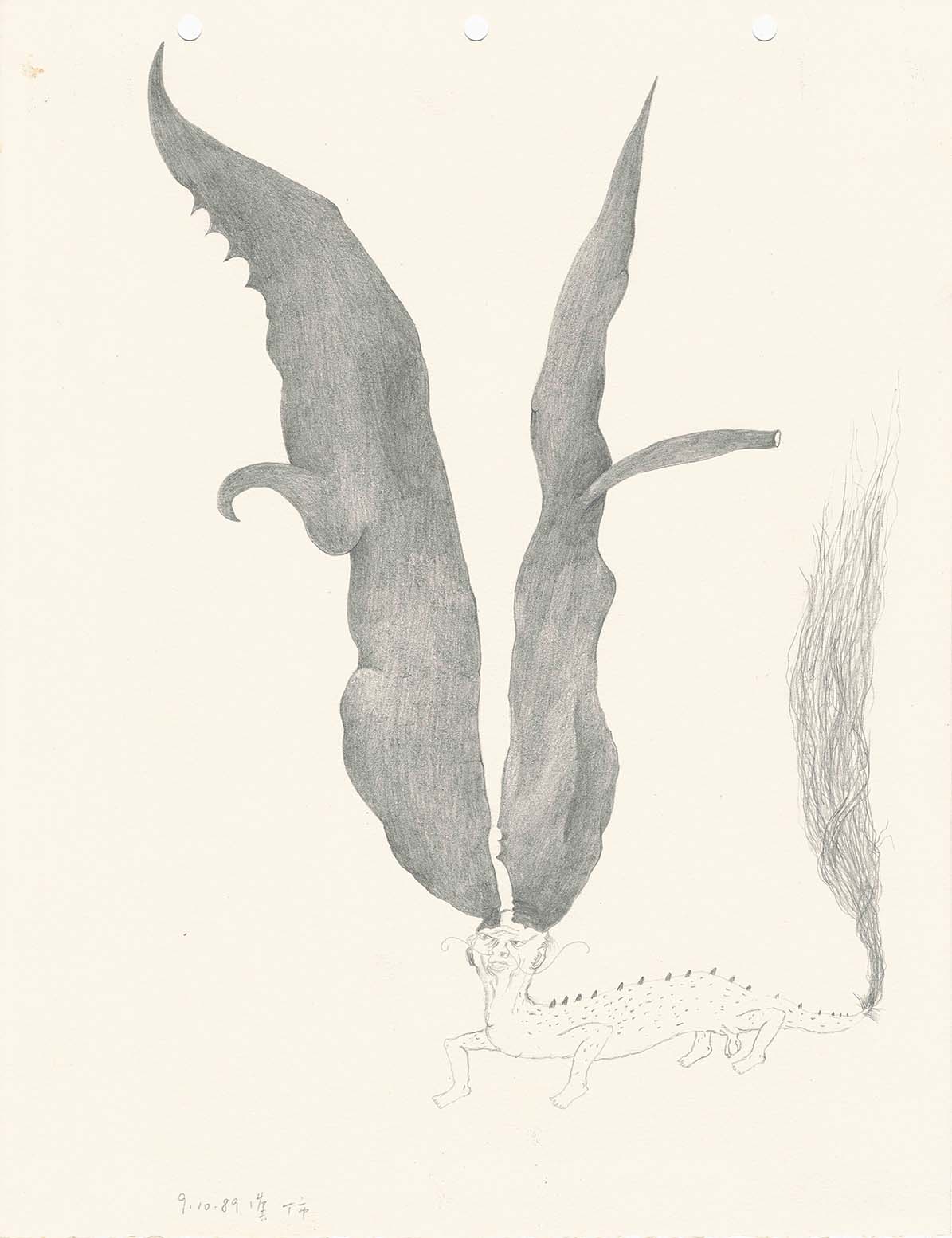

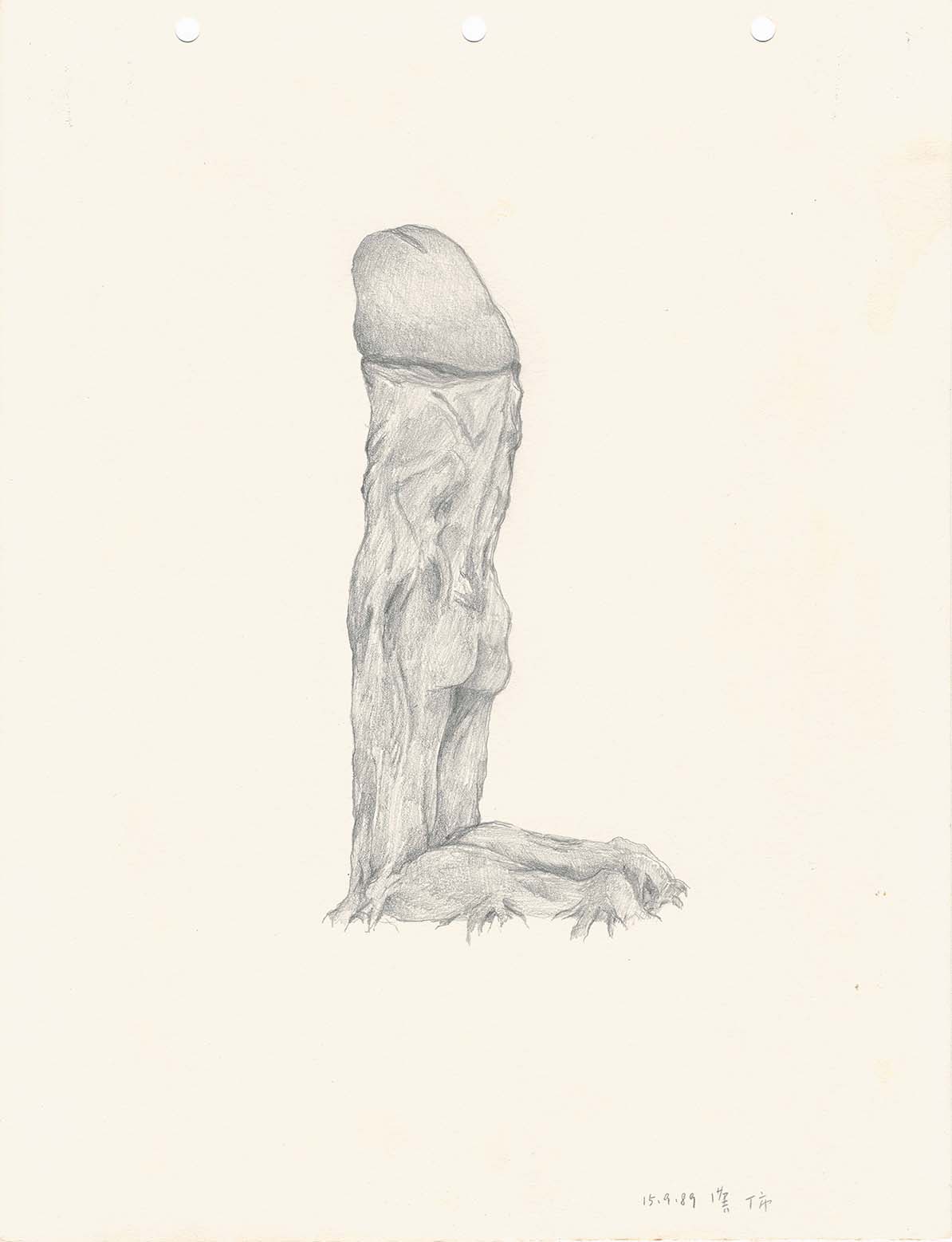

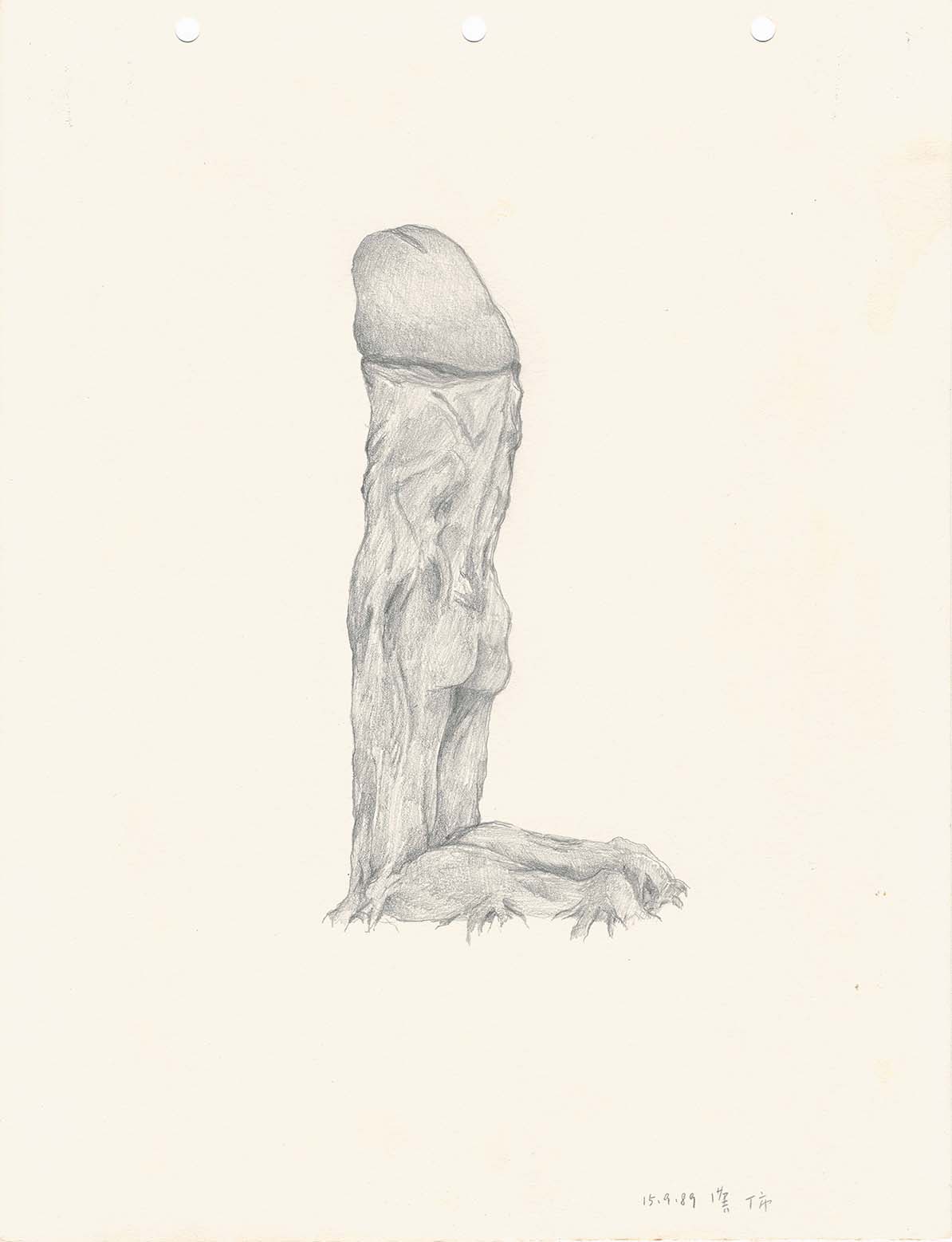

愛用針筆的Rex,這次卻用削得尖尖的鉛筆來創作,追求流暢的線條,並由線織面。這些素描完成度高,但不講究構圖、佈局,畫面都是靜態卻又緩緩流淌,他以畫靜物畫的心思與筆法,呈現古古怪怪的意念:盆栽裡的樹人、頂著樹枝角的異獸、長觸鬚的老虎蘭(圖七)、陽具草(圖八)、蝸牛人,總之,非常超現實。

(圖七:陳漢標。《老虎蘭》。紙本速寫。1989年。)

(圖八:陳漢標。《陽具草》。紙本速寫。1989年。)

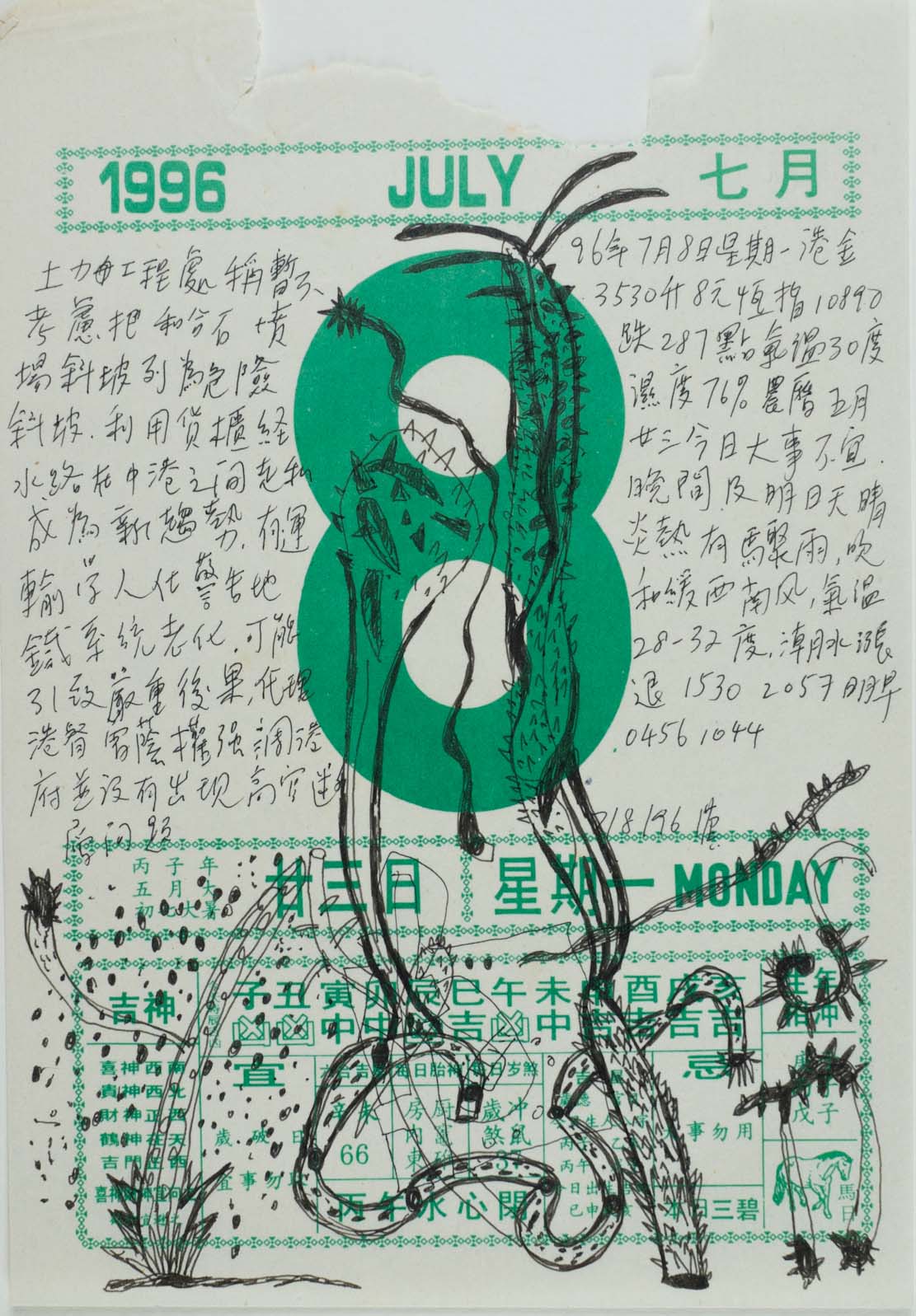

1996年,Rex從加拿大回流,親歷香港回歸。同年,他開始創作紙品拼貼。香港回歸在即,引發了他對「日期」的興趣,於是他開始有意識地收集印有日期的隨手可棄紙品,包括戲票、日曆、機票船票、櫃員機入數紙、郵件、購物單據等等,作為拼貼的原材料。他甚至買了兩份1997年的日曆,一份用來拼貼,一份用來收藏。

早在1980年代中,Rex在小卡上手繪了好些電影院戲票,那時是戲院人手劃座位的年代。他常與理工舊同學王家衛一起看電影,觀影數量驚人,一年超過二百部,那時是Rex歲月靜好的看戲年代。這些帶點戲謔的手繪戲票刻意擬真,又非百分百逼真。興之所至,Rex還曾剪過照相菲林,直接貼到小卡上。

事實上,對於繪描,Rex把玩無厭。1980年代末,早期Mac機系統配置「Imagewriter」,他試著打印圖畫,摸索點陣美學的可能性;他也曾雀躍試用電腦Postscript的文字指令,直接「做」繪描 ;也有些他稱之為「立體drawing」的,是玩著熱熔槍及三維打印筆的實驗。

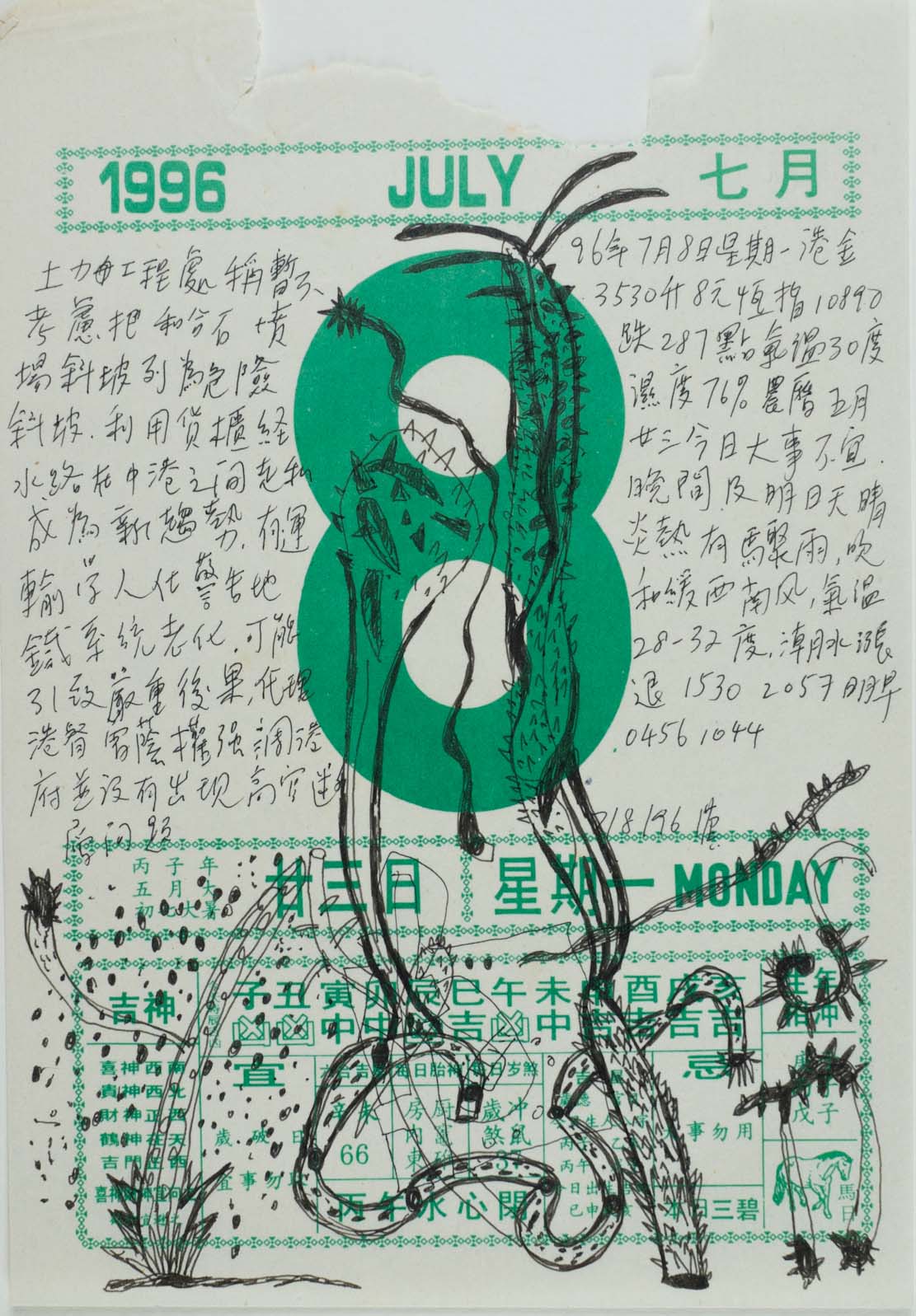

這批拼貼,大抵可以分為兩類。初期,在日曆紙上的塗畫,除了繪描如多牙多腳植物、大號的類單細胞生物,也包含手寫文字,這些文字記下一串串新聞時事流水賬。例如,1996年7月8日的日曆紙上如是記錄:「土力工程處稱暫只考慮把和合石墳場斜坡列為危險斜坡,利用貨櫃經水路在中港之間走私成為新趨勢,有運輸學人仕警告地鐵系統老化,可能引致嚴重後果,代理港督曾䕃權強調港府並沒有出現高官斷層問題」;(圖九)或1996年11月18日:「香港和澳洲航空路線談判破裂,澳洲指責港府採保護主義,九廣鐵路決定將西北鐵路的人手削減至110人,臨立會候選人,今日開始報名,全日共有五十六人索取表格,籌委會副秘書長認為暫時未有政黨及組織可有影響選舉結果」。(圖十)這種刻意不帶情感、等級、輕重的列寫,大有「大時代不就是由小日子構成的嗎」之意。這些塗畫塗寫,成為他表達情感、安頓忐忑和焦慮,並記錄歷史的一種方式。

(圖九:陳漢標。《1996年7月8日》。現成物拼貼,35.5(長)x 25.4(寬)厘米。1996年。)

(圖十:陳漢標。《1996年11月18日》。現成物拼貼,35.5(長)x 25.4(寬)厘米。1996年。)

另一類是Rex在拼貼紙品上盡情塗鴉,圖案、繪描,有時並置,有時層層疊摞。這種厚塗,像是各種各樣文具的「大匯演」:藍色原子筆、紅色原子筆、白色塗改液、麥克水筆 、鉛筆、木顏色,不一而足。如此極致的極多主義(maximalism),產生消解的作用,畫甚麼已變成視覺囈語,違和搭調融為一爐。

Rex一直抱持著「無由來」的叛逆,我想他在尋找非常規的方法,去為那些本來就不明不白的規矩或制約解套。我不禁想起《水滸傳》裡的一句話,也許這是一回不太貼切的比喻,但這個不按常理出牌的畫面,形象化了Rex所說的「無由來」的叛逆精神和態度,驅動著他的藝術實踐:「先把拳頭虛影一影,便轉身,卻先飛起左腳,踢中了。」(圖十一)

(圖十一:陳漢標。《自畫像》。紙本速寫,7.6(長)x 3.8(寬)厘米。1982年。)

註:

[1] 香港視覺藝術協會於1973年成立;創會成員來自當時的香港大學校外課程部藝術文憑課程畢業生。

[2] 1976年的「理工設計」畢業展可說別具意義,不僅是在理工紅磡校園內Keswick Hall舉行的首次畢業展,更以「PolyDesign Show」命名,為建立「PolyDesign

品牌奠定了基礎 。

[3] Rex提到的老師:郭孟浩、蔡仞姿、王無邪、張義、李旭初 、John ROSE、John HIRST、Douglas TOMKIN、Leslie DIXON、Michael TUCKER、Anthony LEE、Alex LAM、Joesph FUNG、Ken HAAS、Margaret CHARLESWORTH及曾鴻儒(陶瓷室技術員)。

[4] 1994年,香港理工學院升格為大學。

[5] 這份教學筆記沒有註明是誰編寫的,筆者相信是在理工執教多年、以繪描樹而見稱的藝術家畢子融所編,他著有《繪描藝術》。畢子融曾表示過:「『繪描』一詞不是我起的,也非我推動,是香港教育界推動的。當年佳藝電視有一個教畫節目,由我們的師姐主持,後找人寫文章結集成《繪描初階》(或稱《繪描之初階》)一書。此書令我印象深刻,每人寫一點光、影、執畫筆的手法,非常初階。『繪描』這名詞由此而生。」(引自黎明海、文潔華編著:《與香港藝術對話1980-2014》[香港:三聯書店,2015],頁226。另,佳藝電視是個短命的電視台,1975年9月啟播,至1978年8月停播。)

[6] 約翰・伯格著;黃華僑譯:《約定》(桂林:廣西師範大學出版社,2009),頁147至48。

[7] 見「默語,札記,符碼:陳漢標,何慶基,和于彭作品展」(漢雅軒主辦,17/9/1988–9/10/1988)宣傳單張。原文:‘His paintings deal with the isolated state of human existence and an escape into an imaginary yet symbolic world where fantastic plants and creatures around. They are often blown up larger than life to assume a monumental presence. His drawings, on the other hand, are immediate notations of an inventive mind, full of whims and surprises.’

[8] Rex的小卡,除了在《星期日雜誌》刊載過,也在不同展覽展示過:「走鬼──漢標作品」(1985),進念‧二十面體銅鑼灣場地,是應林奕華之邀;在「《廿四品》香港設計師協會會員展」(1987),陳漢標展示了八至九本卡片簿;「走鬼2」(1989)等。

(本文原由嚮渡藝術空間委托撰寫,並經李海燕編輯。作者獲授權在此平台刊登,特此致謝。)

Rex Chan - the Sketchomaniac: An Ethnographic Study

by Phoebe Wong

Pulling open the drawers of the drawing cabinet reveals stacks of sketchbooks and all manner of drawings—hand-drawn and non-hand-drawn, flat and three-dimensional. When it comes to drawing, designer Rex Chan navigates between sketching, memory drawing, rendering, illustration and painting.

Sketches, memory sketches, live drawings, illustrations, layouts, and even renderings—these art termscan sometimes be used interchangeably. Yet upon closer examination, they reveal subtle distinctions, all falling under the umbrella of drawing (also known as sketching). Drawing is to design students what free writing is to novelists: a form of self-expression and a preparatory state.

Among these countless drawings, three batches are particularly captivating. Firstly: cards, primarily created between 1982 and 1986, with intermittent additions until 1989, numbering no fewer than 3,000 pieces (Figure 1); second: over thirty pencil sketches from 1989; and, third: collages using printed ephemerals, created since 1996, numbering approximately 240 to date.

(Figure 1: Rex Chan's sketch cards. Image courtesy of the author.)

It was through looking at these three bodies of work that I began my conversation with Rex. Beyond exploring the origins, narratives, and techniques behind these creations, I was particularly interested in understanding the relationship between his background as a designer and his diverse drawing practices. Through our detailed discussions, it became clear that many aspects lacked simplified, deterministic cause-and-effect relationships; at best, one could discern certain correlations. Some memories were buried deep, and even the clues uncovered might only be faint, scattered threads . . . Regardless, we must start with Rex's background as a designer.

Rex pursued liberal arts in high school while self-studying art. In 1977, he enrolled in the Design Department at the Hong Kong Polytechnic (now PolyU). His single-minded determination to study design stemmed from a seed planted during a summer design course at a youth centre. The instructor was artist Victor Li Ki-kwok, who practiced both art and design and was a member of the Visual Art Society (VAS). [1] Although Rex's time in Li's class was brief, the experience laid a solid foundation in design and forged his resolve, making him realise design was a viable career path.

In 1976, living in Sham Shui Po, he visited the ‘Poly Design’ graduation exhibition, its debut on-site exhibition on the Polytechnic’s campus[2]; and, made his way to the Hotel Plaza (later demolished) in Causeway Bay to see the VAS exhibition. Rex had also learned about the VAS through Li. Looking back today, Rex observes that the generation of artists who founded VAS frequently discussed “formative art,” striving to pioneer novel approaches through extensive use of graphic and organic forms. Their work was figurative yet not entirely realistic. Rex believes his own creations embody these same characteristics.

In 1979, Rex completed the Foundation Diploma in Design at the Polytechnic, achieving grades sufficient for advancement to the Higher Diploma programme. However, after six months, he dropped out to pursue employment, feeling the coursework lacked novelty and noting abundant job opportunities outside. When discussing his design professors, Rex can rattle off over a dozen names in one breath—a testament to the profound influence and regard he held for these mentors [3]. Among them, Rex felt he had “the best chemistry” with Kwok Mang-ho (Frog King).

Rex’s initial encounter with Frog King occurred in Li's design class, when Li took students to Yuen Long to see Frog King's art performance activities. They later reunited in the design department. Rex recalls that during their time at the Polytechnic, Kwok employed an open teaching approach. In sculpture-focused classes, he taught wirework and seal carving, encouraging experimentation with any three-dimensional creation. Jewelry design assignments allowed students to craft various accessories, characterized by oversized and exaggerated designs—a student even made a Taoist hat. After submitting work, Frog King then led students on a parade down Nathan Road. Another class event, a “happening” which Frog King translated as “guest arrival,” involved students burning objects in a quiet corner of Tsim Sha Tsui East, near the Polytechnic. Rex admitted he was “convinced” by Frog King's teaching and “grew bolder” as a result; his love for seal carving was also influenced by Frog King.

When considering the teaching of design principles in the 1970s and 1980s, the importance of learning drawing cannot be overlooked. Mastering the depiction of figures, objects, environments, and spaces was a fundamental requirement for aspiring designers. Hong Kong Polytechnic University archives still contain teaching notes on “drawing” written in Chinese by instructors during the 1980s [4] [5] (Figure 2). These teaching notes explain that “…Drawing is a form of visual expression that best conveys an artist's emotions. Because it originates directly from the artist's hand—a direct translation—it remains closest to the artist's inner imagery. Every stroke is a record of the artist transforming the images within their heart into pictorial form.”

(Figure 2: Teaching notes on “drawing” by a Hong Kong Polytechnic instructor from the 1980s. Image courtesy of Siu King-chung.)

This “translation” theory discussed in these teaching notes emphasizes the connection and transformation between the body (hand) and mind (thoughts, imagery), yet it only outlines the concept. This reminds me of Chinese painter Liu Xiaodong, who views live figure drawing as an artistic action. However, Liu seems to merely externalise the expressive aspect of “translation.” It wasn't until I read British art critic John Berger's writings on his beloved sketches—rich in both philosophy and imagery—that the concept of “translation” seemed to gain deeper clarity. Berger, who abandoned painting to pursue art criticism, maintained an unbroken lifelong passion for (figure) sketching. He stated:

“Image-making begins with questioning phenomena and marking symbols. Every artist discovers that drawing—when it is an immediate activity—is a two-way process. Drawing is not only measuring and recording, but also receiving. When the density of seeing reaches a certain point, one becomes aware of an equally intense force surging toward them through the very phenomenon they are scrutinizing. [. . .] The encounter between these two forces, and the dialogue between them, poses no questions or answers. It is a fierce, violent, and ineffable conversation. Sustaining this dialogue depends on faith. It is like digging a tunnel in the dark, digging a tunnel beneath the phenomenon. When these two tunnels meet and successfully join, a [brilliant] image is born. Sometimes the dialogue is swift, almost fleeting, like the throwing and catching of something.” [6]

For quite a long stretch of time, Rex drew sketches on cards daily. As he put it, those day-in-day-out little exercises (of drawing something) were done spontaneously, without much thinking; the pen (line) moved freely, drawn quickly, and drawn often. He would produce “a dozen or so” in an average evening. I tried to trace the origins of this practice, but he had forgotten how it began. Perhaps it was simply that he happened to buy some cards for seal craving, found himself with free time in the evening, and drew as he pleased.

Rex has used two sizes of small cards. The 7.6 x 3.8 cm cards, slimmer than standard business cards, possess an elegant refinement. When drawing on these cards, Rex either explores forms—primarily organic lines—or experiments with materials, drawing and testing repeatedly. He habitually uses fine felt-tip, water soluble marker pensor ballpoint pens, occasionally adding colour. Sometimes he begins by applying colour blocks, then builds forms from the negative space left blank. His compositions range from full (where the subject emerges from a lush wash of ink) to sparse (sometimes just a single line), and also features motifs with a refined design sensibility. Notably, Rex favours a 0.1 technical drawing pen for line-work, reveling in its crisp, stable, and consistent fine lines. Only designers typically master and cherish this tool for drawing.

What does he draw? His subjects are eclectic, but figures and animals dominate. His human models might be strangers encountered in daily life, icons of pop culture, or pure imaginings. Once rendered through memory, they all take on a generic quality. Among the animals, some are bizarre creatures. Even at this early stage, he began sketching strange species reminiscent of The Classic of Mountains and Seas: three-eyed, long-tailed half-human, half-beasts; four-legged flying eagles; bird-headed fish-bodied creatures; strange trees and mythical beasts gradually emerge on the paper. Among these animals, tigers were repeatedly drawn. In 1982 alone, he produced no fewer than fifty tiger sketches, each in a distinct style: freehand brushwork, cartoonish, patterned, folk-inspired, figurative, abstract, partially viewed or fully formed—the variety was endless (Fig. 3 & 4). Rex's tigers never appear ferocious—no bared teeth, no regal intimidation. Sometimes they even carry a hint of childlike innocence. The card dated “1982.08.24” reads, “Dismembering the Tiger” (Fig. 5). It dawned on me that beyond subverting the tiger's image, deconstructing the visual form was also his artistic intent.

(Figure 3 (left), Figure 4 (centre): Rex Chan, tiger-themed cards, sketch on paper, 7.6 cm (length) x 3.8 cm (width), 1982–1983. Figure 5 (right): Rex Chan, dismembered tiger, sketch on paper, 7.6 (L) x 3.8 (W) cm. 1982.)

Moreover, spikes recur repeatedly, like individual components—elements awaiting assembly into a coherent whole. These triangular prickles sometimes consist solely of lines, sometimes appear as small colour blocks, sometimes form part of the background, sometimes transform into tiger claws, and occasionally become elements of postmodern design (such as Memphis-style design). More often, they manifest as tentacles or the spines of vines in myriad forms. Clearly, these spines serve as a metaphor for thorns, becoming a crucial component—even a leitmotif—in his subsequent paintings (Fig. 6). (In Rex's large-scale works, oversized thorns appear prominently in various forms, though this exceeds the scope of this discussion.)

(Figure 6: Rex Chan, spike-themed cards, sketches on paper, each 7.6 cm (length) x 3.8 cm (width), 1982–1983)

Rex is a painting enthusiast and a master of line drawing, yet sketching from life has never been to his liking. He only attended a figure drawing workshop at the Hong Kong Arts Centre once, taking advantage of a work opportunity. When I describe Rex as a ‘sketchomaniac’, he seems unconvinced. Uninterested in television, he paints by lamplight at night. When inspiration strikes, he records the day's sights and thoughts—this is visual journaling, keeping a diary through drawing. While sketching and memory drawing seem opposites, Rex's small cards blend quick sketches, memory drawings, and line drawings, navigating between visual notes and creative markings. In contrast to Berger's notion of an energy exchange inherent in drawing, Rex's nightly solitary memorization and tracings become a self-dialogue where memory and thought leap.

Former Exhibition Director of the Hong Kong Arts Centre, Michael Chen, once interpreted Rex's paintings thus: "His paintings deal with the isolated state of human existence and an escape into an imaginary yet symbolic world where fantastic plants and creatures abound. They are often blown up larger than life to assume a monumental presence. His drawings, on the other hand, are immediate notations of an inventive mind, full of whims and surprises." [7] Chan's perceptive analysis directly identifies sketches as a form of notation—a kind of note-taking. This identification of “notation” is particularly meaningful, as the word carries rich connotations—it can signify symbols, marks, annotations, records, or even musical notation. Moreover, this passage indirectly reveals that sketches serve as footnotes for larger paintings; it is through these accumulated sketches that ideas to be transformed or reinterpreted into expansive works.

Lee Lim-chee, a cultural practitioner who is also a designer, once published Rex's sketch cards in the ‘Sunday Magazine’ of Sing Tao Evening Post (on 11 September 1988), referring to them as “daily assignments”—Rex assigned himself tasks after work, consistently for three, five, or even seven years. Lee Lim-chee admired these exercises for their “spontaneity” and “unfettered freedom.” [8]

These small cards radiate spontaneity, unleashing primal energy, blending beauty and ugliness into one. They accumulate like small streams forming a mighty river. Rex said that his pencil sketches created for the 1989 exhibition were made in response to his sketch-card style—that is, he strived to “draw slowly.” “Slow drawing” became the premise for this series of pencil works. Was he observing, even transcending, his own patience? At that time, he lived in Canada, a place Hong Kong immigrants often found unbearably dull. This series of sketches was completed during his first three months of transition after arriving.

Rex, who typically favoured technical pens, instead used sharply sharpened pencils for this work, pursuing fluid lines that wove surfaces. These sketches are highly accomplished, yet unconcerned with composition or layout. The scenes are static yet slowly flowing. With the mindset and technique of a still-life painter, he presents bizarre ideas: tree-men in potted plants, strange beasts with branches for horns, tiger orchids with long tentacles (Fig. 7), phallic grass (Fig. 8), and snail-men. In short, they are profoundly surreal.

(Figure 7: Rex Chan, tiger orchid, sketch on paper, 1989.) (Figure 8: Rex Chan, phallic grass, sketch on paper, 1989.)

In 1996, Rex returned to Hong Kong from Canada, witnessing the city's transition and handover firsthand. That same year, he began creating paper collages. With Hong Kong's handover imminent, his interest in “dates” was sparked. He consciously started collecting disposable paper items bearing dates—including movie tickets, calendars, plane and ferry tickets, ATM deposit slips, mail, shopping receipts, and more—as raw materials for his collages. He even purchased two copies of the 1997 calendar—one for collage and one for preservation.

(Figure 9: Rex Chan, 8 July 1996, collage of found objects, 35.5 cm (L) x 25.4 cm (W), 1996.) Figure 10: Rex Chan, 18 November 1996, collage of found objects, 35.5 (L) x 25.4 (W) cm, 1996.)

As early as the mid-1980s, Rex drew by hand on numerous cinema tickets on small cards when theatres still manually assigned seats. He frequently watched films with his former Polytechnic classmate Wong Kar-wai, consuming an astonishing number—over two hundred movies a year. Those were the tranquil days of Rex's cinema-going youth. These whimsical hand-drawn tickets strived for realism without being entirely accurate. On a whim, Rex once cut photographic film and directly pasted it onto the cards.

In truth, Rex never tired of exploring line art. In the late 1980s, using the ImageWriter printer on an early Mac system, he experimented with printing drawings, probing the possibilities of dot matrix aesthetics. He also excitedly tried computer Postscript text commands to directly “create” line art. He also began, in what he termed, “3D drawing”—experiments with hot glue guns and 3D printing pens.

These collages can broadly be divided into two categories. In the early phase, the drawings on calendar paper included not only tracings of multi-toothed, multi-limbed plants and oversized, single-celled-like organisms, but also handwritten text documenting a series of news events and current affairs. For example, the 8 July 1996 calendar page records: “The Geotechnical Engineering Office states it is currently only considering designating the Wo Hop Shek Cemetery slope as hazardous. Smuggling via shipping containers through waterways between China and Hong Kong has become a new trend. Transportation experts warn that the aging MTR system may lead to serious consequences. Acting Governor Donald Tsang Yam-kuen emphasises that the Hong Kong government does not face a senior official succession gap.” (Fig. 9). Or, on 18 November 1996: “Hong Kong and Australia break off airline route negotiations; Australia accuses Hong Kong government of protectionism; Kowloon-Canton Railway decides to reduce northwest railway staff to 110; Provisional Legislative Council candidate registration begins today, with 56 people requesting forms during the day; Provisional Legislative Council Preparatory Committee Deputy Secretary-General believes no political parties or organisations currently exist could influence election results” (Fig. 10). These deliberately emotionless, hierarchical, and weightless listings carries the implication: “Aren’t significant periods of time just made up of small days?” These scribbles and graffiti became his way of expressing emotion, soothing his restlessness and anxiety, and recording history.

Another phase features Rex's unrestrained doodling on collage paper—patterns and sketches sometimes juxtaposed, sometimes layered upon each other. This thickly-layered application resembles a “grand parade” of stationery: blue ballpoint pens, red ballpoint pens, white correction fluid, marker pens, pencils, coloured pencils, and more. Such extreme maximalism produced a dissolving effect, where what is drawn becomes visual gibberish—incongruities and harmonies fused into one.

(Figure 11: Rex Chan, self-portrait, sketch on paper, 7.6 cm (length) x 3.8 cm (width). 1982.)

Rex has always held onto a “groundless” rebelliousness. I think he seeks unconventional methods to untangle these inherently obscure rules or constraints. I can't help but recall a line from the classic novel, Water Margin. Perhaps it's an imperfect analogy, but this scene that defies convention vividly embodies the “groundless” rebellious spirit and attitude Rex speaks of, driving his artistic practice: “He first flashed a shadow of his fist, then spun around, swiftly kicking out with his left foot to strike his target.” (Fig. 11)

Notes:

[1] The Hong Kong Visual Art Society was established in 1973; its founding members were graduates of the Diploma in Fine Arts programme offered at the time by the University of Hong Kong's Extra Mural Studies department.

[2] The 1976 Polytechnic Design graduation exhibition holds particular significance. Previous exhibitions had been held off campus, this was the inaugural graduation show held at Keswick Hall, on-site and within the Polytechnic's Hung Hom campus. It was also named the “PolyDesign Show,” laying the foundation for establishing the “PolyDesign” brand.

[3] Teachers mentioned by Rex include: Kwok Mang-o, Choi Yan-chi, Wucius Wong, Cheung Yee, Li Yuk-cho, John ROSE, John HIRST, Douglas TOMKIN, Leslie DIXON, Michael TUCKER, Anthony LEE, Alex LAM, Joseph FUNG, Ken HAAS, Margaret CHARLESWORTH and Tsang Hung-yu (ceramics studio technician).

[4] In 1994, the Hong Kong Polytechnic was elevated to university status, and its name became The Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

[5] This teaching manual does not specify an author. I believe it was compiled by artist Aser But, who taught at the Polytechnic for many years and was renowned for his tree drawings. But authored The Art of Drawing. Aser But once stated: "The Chinese term of ‘drawing’ was neither coined nor promoted by me, but by Hong Kong's education sector. Back then, Commercial Television aired an art instruction programme hosted by one of our senior classmates. Later, they commissioned articles compiled into the book Drawing Fundamentals. This book left a deep impression on me—each contributor wrote about light, shadow, and brush techniques, all very basic. The Chinese term ‘drawing’ thus came into being." (Quoted from Lai Ming-hoi and Man Kit-wah, eds., In Conversation with Hong Kong Art 1980-2014 [Hong Kong: Joint Publishing, 2015], p. 226. Note: Commercial Television (CTV) was a short-lived broadcaster, operating from September 1975 until its closure in August 1978.)

[6] John Berger, Keeping a Rendezvous (Originally published in English by Granta, 1992).

[7] See the leaflet for “Private Notes: Works by Rex Chan, Oscar Ho, and Yu Peng” (exhibition organised by Hanart TZ Gallery, 17/9/1988–9/10/1988).

[8] Rex's cards, besides appearing in ‘Sunday Magazine’, were also exhibited in various shows: “Running from Ghosts: Works by Rex Chan” (1985) at Zuni Icosahedron's Causeway Bay venue, at the invitation of Edward Lam; in “Twenty-Four Pieces: Hong Kong Designers’ Association Members’ Exhibition” (1987), where Rex Chan displayed his card-sketch albums; “Running from Ghosts 2” (1989), among others.

(The Chinese text was originally commissioned by To Art House and edited by Joanna Lee. The author has permission to publish it on the AICAHK website, for which we extend our gratitude. The English text has been added & edited by AICAHK and the author.)