藝評

Sam Francis and Walasse Ting: An Artistic Friendship

祈大衛 (David CLARKE)

at 10:36pm on 11th January 2022

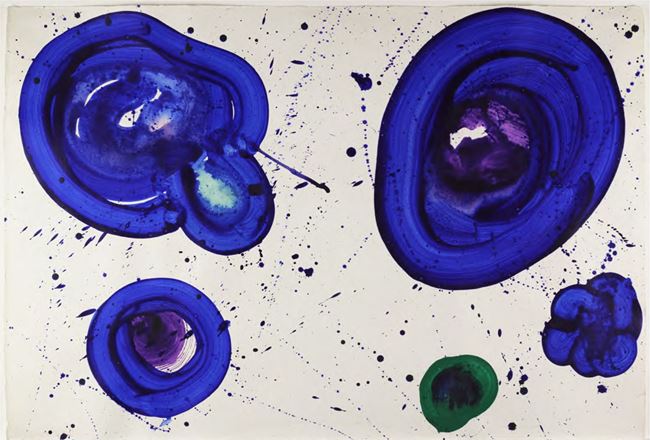

1. Sam Francis, Blue Balls, 1962

50 x 73 cm

19 11/16 x 28 3/4 inches

Courtesy Alisan Fine Arts. © 2020 Sam Francis Foundation, California/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

56.5 x 76 cm

22 1/4 x 29 15/16 inches

Courtesy Alisan Fine Arts.

(一篇關於美國抽象藝術家山姆·弗朗西斯和華裔畫家丁雄泉之間友誼的文章,後者大半生都在美國和歐洲渡過。)

Whether we consider first generation abstract artists such as Wassily Kandinsky or Piet Mondrian, or their counterparts in the second half of the twentieth century such as Pollock and Rothko, an engagement with water or with the property of fluidity it exemplifies was often crucial to the evolution of their mature styles. While there were certainly other routes beyond bounded form which artists could follow, such as the path of fragmentation adopted by those who made the Cubism of Picasso and Braque their stepping stone to the abolition of solidity, for many it was the path of dissolution which was favoured.[i] Amongst those artists of that second wave of abstraction for which watery dissolution was the way of liberation is Sam Francis (1923-1994). Perhaps influenced by the multiform images that Rothko produced during his own movement beyond the representational image, Francis also moved to a more fluid way of working, and in his later work a liquid feel is rarely absent. Splashed marks are often utilized: one feels that Pollock is an influence here but the look is entirely Francis’s own. As the artist Gordon Onslow-Ford puts it, ‘one painter upsets a pot of paint in one way, another painter upsets a pot of paint in another way’ – the chance mark still serves the particularity of a given artist’s expression.[ii]

We already observe an increased spontaneity of brushwork in the early Impressionist painting of Claude Monet – a broken brushwork which is self-evident to the eye as brushwork. But such marks are still controlled by the hand to a large degree. Deliberate acceptance of chance marks in a finished painting seems first to come in European art at the very beginning of the twentieth century, with a dribble of wet paint at the lower edge of Paul Cézanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire (1902-6, Zurich Kunsthaus) being one early example, and the more extensive dribbles in Henri Matisse’s Dance (I) (1909, MoMA, New York) being another of slightly later date. With Sam Francis, however, the splashed or dribbled mark has become a central part of the syntax of the work in a way these earlier painters would never have contemplated. When he began experimenting with such a watery vocabulary it came as something of a revelation for him. ‘The first time I started playing with liquid paint [he stated], letting it fall, […] it ran off the paper, on the sheets, onto the floor. It was really nice, […] a great feeling’.[iii]

Although many of Francis’s breakthrough works were made using oil paint, watercolour played a significant role in his artistic development, and when acrylic paints became available he took to that other water-based medium as well. At the level of inspiration rather than personal practice, Chinese and Japanese painting - which had always given water-based mediums a centrality they never had in European art - was also an influence on the fluidity of his work. Although Francis was not in the habit of giving many interviews or authoring published statements about his art an interest in Asian thought is confirmed by his friend Walasse Ting (Ding Xiongquan, 1929-2010), and the deep connections he formed to Japan are well known.[iv]

Given this deeper interest in Asian thought it is not too much to suggest that the fluidity of Sam Francis’s style can be read as metaphoric of a world view which de-emphasizes solidity in favour of process and insubstantiality. His images seem to embody a cosmological picture consonant with that of Buddhism, which speaks of the impermanence of all phenomenal reality, an absence of substance.[v] A preference at certain points for allowing an empty whiteness to predominate in the image, with pigment largely relegated to the edges (as in Blue Cut Sail of 1969 or Bright Ring Drawing of 1965), makes this engagement with philosophical notions of the void most clear. I would argue, though, that it is present even in works such as Untitled 5 of 1978, which has a grid-like compositional armature. Although the grid, so commonly found in modern Western art, might seem to signify structure, in the work of Sam Francis this familiar motif is invoked only in order to be undermined.[vi] Fluid mark making serves to erode and dissolve the rigid architecture of the grid, allowing process to trump substance.

In the exhibition Celebrating a Friendship (20 January to 20 March, 2021), Hong Kong art gallery Alisan Fine Arts brought together works on paper by Sam Francis and his friend Walasse Ting, allowing comparison to be made between two artists for whom colour played a central role. Ting, a Chinese-born painter who cut ties with his homeland and spent his later life in Europe and the United States, had extensive contacts in the art scenes on both sides of the Atlantic. We may not yet have a full picture of the role he played in cross-cultural artistic exchange at a time in the later 1950s and early 1960s when many Western artists were open to exploring East Asian approaches to painting, but certainly both Pierre Alechinsky and Dan Flavin were to learn from Ting’s understanding of the Chinese brush.[vii] While in Europe Ting made contact with several of the CoBrA group artists, and the array of artistic connections he had established by his early New York years can be demonstrated through the range of artists included in his artist book project 1¢ Life (1964). It is striking that his personal artworld not only bridged continents but also the not insignificant divide between Abstract Expressionist or Tachiste painting and the newly emergent trend of Pop Art. In addition to Alechinsky, Karel Appel, Asger Jorn, and other European artists there were lithographs contributed to accompany Ting’s own poems in 1¢ Life by American artists Sam Francis, Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg and Robert Rauschenberg, amongst many others. Since all these works are included within the covers of the same book (which was displayed in the Alisan Fine Arts exhibition), and juxtaposed with Ting’s poems even on a single page, one can think of this as an extensive artistic collaboration. Such collaborations on the same surface are of course a commonplace idea in earlier Chinese art, and Ting may have been partly inspired by that traditional practice, which would often (as here) lead to words and images featuring side by side.[viii]

Ting engaged in artistic collaboration on other occasions too. Aleching (a lithograph of 1963) is one of several images he produced in collaboration with Alechinsky - it is titled by a conflation of their two names). Jorn’s Grave? (1970-93, acrylic on paper, mounted on canvas, Museum Jorn, Silkeborg, Denmark) involved contributions by both Ting and Alechinsky to an image begun in 1970 by Jorn and Alechinsky, but completed by Jorn’s friends at a much later date, subsequent to his death. Although this author has never seen a completed artwork created in collaboration by Sam Francis and Walasse Ting, intriguingly there is video evidence of the two artists working together on the same surface in 1988, in the former artist’s California studio.[ix] Neither the Sam Francis Foundation nor the estate of Walasse Ting apparently have records of any extant joint work, but the possibility remains open that such images might exist.

Much of Ting’s later work is figurative in nature, and thus differs from that of Francis who pursues abstraction unremittingly in his mature work. Although Ting shares with Francis an interest in applying paint in splatters, in his case the more freely applied thrown paint often tends to remain a clearly distinct second phase of working that comes after an image has been produced with the brush (see for example Three Birds on a Branch, which dates to the 1990s). Such aleatory marks therefore tend to read as a complication or even defacement of the original image, rather than an integral part of its fundamental syntax as they do with Francis. Although one is tempted to compare these later colouristic works by Ting to the equally colourful images of Francis, in some respects it is his earlier calligraphic abstracts from the later part of the 1950s which are more comparable. Although these tend to be monochrome in nature (and thus retain a stronger link to Chinese artistic precedents), they often display a greater gestural energy than his later works and splattered paint is more central to the painterly vocabulary employed. These works, such as the oil paintings My Memory is too Much of 1958 and Chinese City of 1959, belong to a time when artists from a variety of cultural backgrounds were particularly open to learning from other cultures, and a time in which such cultural bridges often took the form of personal friendships between individuals as much as classical texts being read in translation or acknowledged artistic masterworks being viewed at first hand.

A version of this essay was first published as ‘A Friendship: Sam Francis and Walasse Ting’ in Asian Art News, Vol. 30, No. 4, 58-61.

[i] I discuss water as a subject and medium for art in my book Water and Art (London, Reaktion Books, 2009). The engagement with water and dissolution on the path to abstraction is dealt with in chapter three.

[ii] Gordon Onslow-Ford, Painting in the Instant, London, Thames and Hudson, 1964, p. 89.

[iii] Pontus Hulten, Sam Francis, ex.cat., Bonn, Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 1993, p. 21.

[iv] In a letter to the author of 22 July 1980 Walasse Ting wrote: ‘About Sam Francis I think he likes Zen. Less is more. Life as a cloud floating anytime everywhere, take easy, follow as Water to change, if you ask Sam Francis himself that he cannot say in words. He just living as blue water’. Apart from Ting’s confirmation of his friend’s interest in Zen, it is noteworthy that he chooses to use watery metaphors to describe him. On Sam Francis and Japan see Richard Speer, The Space of Effusion: Sam Francis in Japan, Zürich, Scheidegger and Spiess, 2020.

[v] I discuss the way in which Sam Francis and other American artists can be seen as evoking the cosmological picture of traditional Asian thought in my book The Influence of Oriental Thought on Postwar American Painting and Sculpture, New York, Garland, 1988.

[vi] One starting point in the art historical discussion of the grid in modern and contemporary art is Rosalind Krauss, ‘Grids’, October, Summer 1979, p. 50-64.

[vii] Both Alechinsky and Flavin acknowledged an artistic dept to Ting. On Alechinsky see Chang Ming Peng, ‘Walasse Ting and Collective Creation’, in Éric Lefebvre and Mael Bellec (eds.), Walasse Ting: The Flower Thief, Paris, Musée Cernuschi, 2017, p. 47 (this multi-author publication as a whole is a useful resource for the study of Ting’s art). On Flavin see Tiffany Bell and Michael Govan, Dan Flavin: The Complete Lights, 1961-1966, New Haven, Yale University Press, 2004, p. 20. Flavin’s Untitled (Tenements in the Rain) of 1959 is an example of the kind of work Flavin produced under Ting’s influence.

[viii] For a discussion of inscription on Chinese painting see for instance Michael Sullivan, The Three Perfections, New York, George Braziller, 1980.

[ix] See the YouTube video at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z01Sq3MQE9k&t=324s (accessed 21 January 2021). Another video from the same year shows Ting working alone in Sam Francis’s studio: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5INTD5nNvhc (accessed 21 January 2021). For a detailed discussion of the friendship between Sam Francis and Walasse Ting see John Seed, ‘DEAR Big SAM’, Arts of Asia, Vol. 48, no. 5, September/October 2018, p. 84-93.