藝評

Encountering Hong Kong at the museum

彭綺雲

at 4:56pm on 13th May 2013

Captions:

1. (From left) Unidentified, David Lam, Lui Shoukun (Lui Shou-kwan) and Hon Chi-fun, with Angeli Cheng (secretary to the Circle Art Group)(左起)林鎮輝、呂壽琨、韓志勳及中元畫會秘書程潔瑜。Photo courtesy Hon Chi-fun.

2. David Lam at work on a mural for the then Hilton Hotel (c. 1965). Photo courtesy David Lam Chun-fai

3. The mural in the Hilton’s Hong Kong Room, c. 1967. Photo courtesy David Lam Chun-fai.

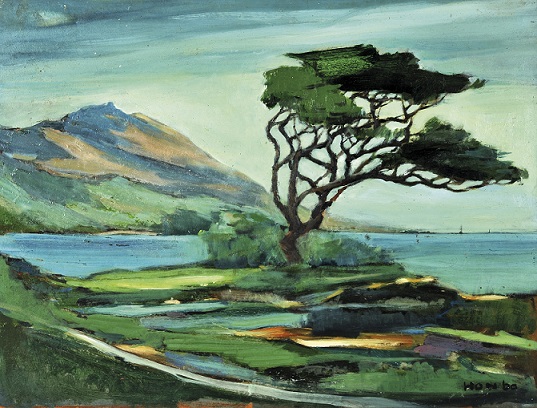

4. Hon Chi Fun, Shek O, Oil on board, 1960. Collection of the artist. 韓志勳 板上油彩。

5. Lui Shou-kwan (Lü Shoukun) (1919–1975), Houses and Squatters’ Huts on Hong Kong (Aberdeen, Hong Kong), Ink and colour on paper, April 1967. The Khoan and Michael Sullivan Collection. 呂壽琨水墨設色紙本, 一九六七年四月, 蘇立文、吳環伉儷珍藏。

(原文以英文發表,評論香港大學美術博物館近期的幾個展覽。)

Beginning in November 2012, the University Museum and Art Gallery of the University of Hong Kong, through an interweaving of pre-existing programming and opportunistic intent, has had an unusually Hong Kong-focused winter. First with “Full Circle: Paintings by David Lam”, a retrospective exhibition of the self-exiled Hong Kong artist David Lam Chun-fai, (林鎮輝, 1932-2013) which ended in March, just weeks after the artist passed away in British Columbia following a spirited battle with cancer. An active member of artist circles in Hong Kong from the 1950s until 1965 when he and his wife, Rose, emigrated to Canada. Lam at first continued to participate in the annual exhibitions of the Circle Art Group by sending his entries in by post. Nevertheless, he can be said to have relinquished a position in the Hong Kong canon, turning away from the place of his becoming towards Canada where he eventually achieved his ambition of becoming a professional artist.

Beginning with his early ink and colour works of Hong Kong in the late 1950s and early 1960s, the exhibition included his experimental segmented Canadian landscapes in watercolour – a period in which he was transitioning between his two art worlds – to his mature acrylics that make intimate and unthreatening the vast Canadian natural world: the waves encountered between the mainland and Vancouver Island, the lifecycle of the sockeye salmon, and his surrealistic juxtaposition of motifs from east and west. Scattered among these works were paintings inspired by his later travels to China. Aware of the timelessness of scenes of Hangzhou’s West Lake, he introduced objects from contemporary life into his compositions as a visual clue to their present.

The exhibition fulfilled the artist’s desire to return to the land of his birth, and to show here what his life as an artist over the past fifty years had become. After the exhibition opened, he wrote that people may have visited the exhibition and wondered, “David who?” Yet, it was as if David Lam had never left Hong Kong, for the paintings that stimulated the greatest discussion among other artists were the ink and colour works he painted of a modernising Hong Kong before he left for Canada. These works are skilful, spontaneous, confident compositions that lend themselves to graphic reproduction, a fact recognised early on by the Hong Kong Tourist Association. In the 1960s, he was represented by the Chatham Art Gallery, and achieved some success. In around 1965, he was commissioned to paint a monumental mural in this style for the Hong Kong Room of the Hong Kong Hilton, the territory’s first, and for many years, only five star hotel, built in 1963. It was eventually demolished in 1995 to make way for the Cheung Kong Building, presumably taking the work with it, though David wondered if anyone had saved it.

In January, as his energy levels became more precarious, David wrote to that he had received a letter from his friend, Hon Chi-fun (Han Zhixun 韓志勳, b.1922), about an exhibition that we were working on inspired by “Full Circle”. He was excited that two old friends would be exhibiting side-by-side again after all these years. David Lam and Hon Chi-fun last exhibited together in the 1960s.

So it was that the exhibition “Hon Chi-fun: Early Landscapes on Board”, which ran from January to March 2013, came about. Built around a collection of landscapes of Hong Kong made during the late 1950s and early 1960s acquired by the museum in 1999, but never shown, the exhibition ruminated upon that era, when Hon was finding his way artistically and like David Lam had not yet settled on the language of his maturity. These exuberant oil paintings are uniformly sized, determined by how a sheet of board is divided, mostly for reasons of portability. Created hastily, they belie their self-taught origins, and show an artist in a hurry to give form to his ideas, before he moves on to the next. They occupy a discreet place in the artist’s oeuvre bounded by the year 1960 indicated in the exhibition by “Script Remote”, when Hon makes an abrupt turn towards greater experimentation. After that, these evocative and haunting landscapes belong to his past.

Hon Chi Fun, Script remote, Oil on board, 1960. Collection of the artist. 韓志勳 板上油彩。

The exhibition proposed that Hon’s later abstract practice has foundations in this training in western oils, as well as Chinese brush and ink, in particular his practice of calligraphy. His friendships with the artists Luis Chan (陳福善 1905–1995) and Lui Shou-kwan (呂壽琨 1919–1975) appear very present in these parallel practices. After 1960, he abandoned oil for acrylic, board for canvas and expanded his technical repertoire to include printing and collage. He never however abandoned his calligraphy, examples of which were shown alongside his ink stones that the artist wrought from duan and other stones. These were a revelation. The strength of Hon’s calligraphic compositions may well be that they offer a more direct channel to the artist’s emotional world than the visual immediacy of his paintings ever can.

The third exhibition, which opened in late February, was a selection of twentieth century art from the collection of the renowned art historian of China, Michael Sullivan (蘇立文, b.1916), and his late wife Khoan (吳環, d.2003). The exhibition was the first time that the collection had been shown in Hong Kong and was put together in a matter of months, made possible only through the enthusiasm and generosity of Professor Sullivan himself. It was sponsored by the University of Hong Kong Museum Society and Michelle Art Services.

Parts of the collection had recently been exhibited at the National Art Museum of China (中國美術館 NAMOC) by the newly established National Research Centre for Modern Art in Beijing in September 2012, so the Hong Kong exhibition benefited from the research conducted in preparation for that. In particular through the consideration of the development of Michael’s career in relation to the collection. If there can be said to be a point of convergence between the three exhibitions, it is Hong Kong c. 1960, glimpsed through the relationships between artists, art historians, curators, gallerists and collectors.

At a time when art historical interest in China was confined to archaeological enquiry and the connoisseurship of ancient paintings, Michael Sullivan was documenting and writing about what living artists in China, Malaya (where he founded the University Museum), Hong Kong and Taiwan were doing. Beginning humbly when Michael was collecting materials for his research, the collection has been formed through a combination of gift, bequest and acquisition and represents both historical interests and personal relationships. It has also been informed by his occasional role as a curator.

Featuring artists that the couple met in Hong Kong, some of them refugees from China, the exhibition included many well-known artists that were trying to resolve the confrontation between western modernity (via Japan and France in particular), and traditional media. Of note in the Hong Kong context are two paintings of Hong Kong by Lui Shou-kwan. One painted in the early 1960s depicts a sparsely populated island adrift in the harbour and dwarfed by its peaks. The other is a large densely-painted hanging scroll, with a modicum of open harbour in the foreground, the composition quickly changes tone to become one of claustrophobic containment as we enter an airless valley with no place to go. Lui’s commentary on social inequality and the poor living conditions of recent migrants, is as valid today as it was in the 1970s. Lui’s own precarious financial circumstances were poignantly detailed in a letter to Michael in the exhibition.

The exhibition also offered a chance to see two rarely shown albums created in 1968 and 1970 by artists in Hong Kong for Khoan and Michael. The importance of seeing the physical object versus reproduction could not have be made clearer. These albums are remarkable in the care with which they were constructed and a significant indication of the regard in which Khoan and Michael have were held in artist circles in the 1960s and early 1970s. The earlier, smaller album includes artists Cheung Yee (Zhang Yi 張義, b. 1936), Hon Chi-fun, Van Lau (文樓, b. 1933), Wucius Wong (Wang Wuxie 王無邪, b. 1936), Lui Guosong (劉國松, b. 1932), and Harold Wong (Huang Zhongfang 黃仲方, b. 1943), in various media, while the latter is an album of works only in ink including Irene Chou (Zhou Luyun 周綠雲, 1924–2011), Lawrence Tam (Tan Zhicheng 譚志成, 1933– 2013) and Ng Yiu-chong (Wu Yaozhong 吳耀中, b. 1935).

Ending in April, the cumulative impact of these three exhibitions has been to remind us of how valuable the process of looking back can be to understanding where we are.

Exhibitions:

Full Circle: Paintings by David Lam

Hon Chi-fun: Early Landscapes on Board

Encounters: Twentieth-century Chinese Art from the Khoan and Michael Sullivan Collection