藝評

奧利奧停戰 | An Oreo Truce

約翰百德 (John BATTEN)

at 11:54am on 22nd May 2018

圖片說明 Caption:

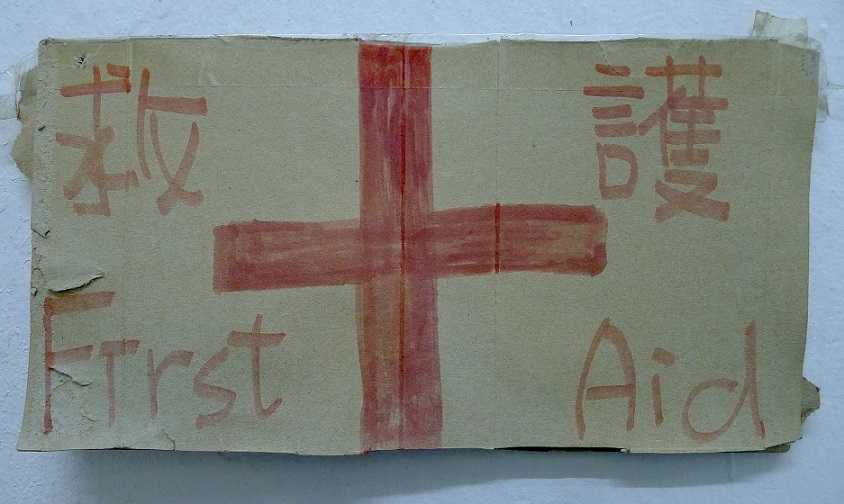

1. 2014年的手繪救護指示牌(約翰百德藏品)/ Hand-drawn First Aid sign, 2014 (John Batten Collection)

2. 手繪救護指示牌背面 / Back side of the cardboard First Aid sign

3.1920年代的瓶架(約翰百德藏品)/ A bottle rack, circa 1920s (John Batten Collection)

(Please scroll down for English version)

在黃竹坑先後開設藝廊和辦公室十二年後,我決定搬離這區。我的大掃除正進行得如火如荼。我有點儲物狂心態,所以清理舊物絕非小工程。這樣說也許不完全正確,因為我沒有把所有可以觸及的東西都收起來。但是,我會紀錄那些自己看過、籌辦過或參與過的活動,也會收起自己寫過文章的點點滴滴。我想,這可以算是一個沒有嚴謹整理過的儲存庫,就那樣疊起來放在書架上和收在箱子裡;是我近期工作生涯的概要。裡面全都是實體物件,主要是紙張:場刊、小冊子、報章、邀請卡、在街上搜來的指示牌和瑣碎物品,還有數之不盡的藏書。這些物件堆積如山,令人頭痛。我和很多香港人一樣有著儲存空間嚴重不足的問題。

諷刺的是,雖然數碼型態帶來很多方便,但我的舊電郵和Facebook Messenger 對話卻更難歸檔封存。我沒有信心它們將可以抵受未來的技術「提升」。我有很多1990年代的電郵,收藏在我的Eudora(早年流行的電郵軟件)郵箱裡,它們早已在更好的科技和長江後浪推前浪的軟件中湮沒。到了今天,我們可以把東西收藏在「雲」中,還在曾經嚴格限制儲存大小的主機伺服器上享有無限制儲存空間。然而,這些無上限的儲存空間也有其局限性:我可不需要儲起自己所有網上留言––連我自己都不會對「嗯 」、「噢」這些電子感嘆詞有興趣!我堅信只消一次停電或在未來網上出現襲擊時,這些東西都會全被刪除掉。諷刺的是如果實體紙本紀錄能抵受潮濕、火災和蟲害,在遙遠的未來中,可能有較大機會遺存下去。

我在箱子之間找到不少寶藏。例如在香港百貨公司大減價時購入的法國乾瓶用架子(見圖3),它應該是1920年代的產物,類似法國藝術家杜尚(Marcel Duchamp)《瓶架》作品中的主體。杜尚在1914年把瓶架形容為藝術品,並稱其為「現成品」藝術,即富藝術氣息的普通製成品。杜尚是首位想出這種革命性、慨念性意念的藝術家,理念與當時其他超現實藝術家的荒謬主義意念不謀而合,而且延伸了他們的想法,為視覺創意開創了更多可能性。我那個小小瓶架令我想起藝術史上那個關鍵時刻。

我在辦公室找到的,還有一袋手寫指示牌和單張,是我於2014年雨傘運動最後一天收集而來。其中一件是一個簡單硬卡紙指示牌,上面畫了一個紅色十字(見圖1)。物件性格鮮明:救護指示牌當時放在佔領範圍內其中一個帳幕上,為所有需要醫療護理人士提供義務協助。它令我們想起那些充滿友愛、希望,然後變成錯失樂觀主義的日子。近日接連出現的雨傘運動抗議人士檢控、撤銷立法會議員資格,還有政府和內地強力譴責任何港獨情緒,已把那些聯想與心情逐漸淹沒。

翻到救護指示牌背面(見圖2),你可看到它本來是簡陋的奧利奧餅乾包裝盒子。把盒子畫成指示牌的小孩,一定有先把餅乾吃掉!我們的建制會害怕這些吃餅乾的前抗議人士嗎?香港應該如何走下去,才可修補那些在2014年打破的圍籬? 林鄭月娥最近出席了民主黨的晚宴;她的政府可以繼續釋出善意:邀請幾位前抗議人士一同喝下午餐,分享大家都應該喜愛的東西,好好享用餅乾。

原文刊於《明報周刊》,2018年4月28日

An Oreo Truce

by John Batten

After more than twelve years of having an art gallery and then office in Wong Chuk Hang I have decided to move. I am now in the middle of a big clean-up. This is no small task. I am a little bit of a hoarder. That’s probably not exactly correct, I don’t keep everything that that comes to hand. But, I do try to keep a record of the many events I have seen, or organized or participated in as well as the many bits of writing I have done. It is, I suppose, a loose archive stacked on shelves and saved in boxes; a summary of my recent working life. It is all physical stuff, mainly paper: programmes, pamphlets, newspapers, invitation cards, signage and ephemera collected on the street – and, countless books. All this accumulated clutter gives a headache – I have the usual Hong Kong problem of too little storage space.

Ironically, despite the convenience of the digital format, my old emails and Facebook Messenger conversations are potentially harder to archive. I am not confident that they will survive future technological ‘improvements’. The emails saved in my old Eudora - an early email software program – mailboxes from the 1990s were overwhelmed by better technology and supplanted software. Nowadays, we have storage options in the ‘cloud’ and unlimited capacity on host servers that previously had strict storage limits. However, this unlimited storage capacity is also restrictive: it is not necessary to save my every online comment – even I’m not interested in my “mmmh!” or “oh!” electronic exclamations. I am convinced that a simple power outage or the zap of a future cyber-attack will delete the lot. It is ironic that physical paper records might, if they survive humidity, fire and pestilence, be more likely to survive into the distant future.

In between my boxes of stuff I found some treasures. At a Hong Kong department store discount sale I bought a French bottle drying rack (picture 1), supposedly “circa 1920s.” It is similar to the type French artist Marcel Duchamp entitled Bottle Rack, and which he described in 1914 as an artwork and termed a “readymade” – a commonly manufactured item that was presented as itself as an art object. Duchamp was the first artist to conceive such a revolutionary, conceptual idea. This matched and extended the absurdist ideas of other surrealist artists at the time and opened-up further possibilities for visual creativity. My own modest bottle rack is a reminder of that pivotal moment in art history.

Also found in my office was a bag of hand-written signs and leaflets that I collected on the last day of the Umbrella protests in Admiralty in 2014. One was a simple sign of a drawn red cross and text on cardboard (picture 1). This was a poignant object, a First Aid sign which had been stuck to one of the area’s tents offering volunteer assistance to anyone needing medical care. It was a reminder of those days of camaraderie, hope and then of failed optimism. Drowning out those sentiments have been recent prosecutions of Umbrella protesters, the disqualification of legislators and strong government and mainland denouncements of any sentiment for Hong Kong independence.

Turn over the cardboard First Aid sign and you’ll see it’s written on a flimsy container of Oreo biscuits (picture 2). The kids who wrote this sign would surely have eaten the biscuits first! Is the establishment frightened of such biscuit-eating former protesters? How can Hong Kong move on and repair those broken fences of 2014? Carrie Lam recently attended a Democratic Party dinner; her administration could continue this goodwill: invite a few former protesters for afternoon tea and share something they should have in common: the enjoyment of eating biscuits.

This article was originally published in Ming Pao Weekly on 28 April 2018. Translated by Aulina Chan